On May 24, 2020, Benjamin Netanyahu walked into a courtroom in Jerusalem to face charges of corruption. The occasion was momentous by any measure — Mr. Netanyahu became the first sitting Israeli prime minister to stand trial. But despite these historic charges, the media appeared equally fixated on what Mr. Netanyahu was wearing. Why? He walked into court donning a blue surgical facemask, consistent with public health restrictions for the coronavirus.{1} 1 See P. Goldman & S. Smith, Netanyahu Stands Trial on Charges of Bribery, Fraud and Breach of Trust, NBC News (May 24, 2020), https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/netanyahu-stands-trial-charges-bribery-fraud-breach-trust-n1212806. And Mr. Netanyahu was not alone. All of the lawyers and judges in attendance also wore masks, while the three-judge panel positioned themselves behind a glass divider.{2} 2 See id. Few have considered how these changes will impact Mr. Netanyahu’s trial, but none can deny that the stage for one of the biggest trials in the world had been fundamentally altered.

This is no isolated incident. The COVID-19 pandemic is transforming the world’s legal institutions with alarming speed. In the United States, many federal and state courts have indefinitely suspended most in-person proceedings, including a near-total shutdown of criminal and civil jury trials, to limit the spread of the coronavirus. In view of health concerns, some trials were even halted mid-testimony, with judges declaring mistrials to limit the risk of infection.{3} 3 See M. Crane-Newman, NYC Sex Abuse Case Ends in Mistrial After Defense Lawyer Shows Up with Coronavirus Symptoms, N.Y. Daily News (Mar. 16, 2020), https://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/manhattan/ny-manhattan-judge-mistrial-covid-20200316-e625abx3k5axfdki3tu5ou7xuu-story.html (declaring a mistrial when defense counsel exhibited COVID-19-type symptoms when struggling to examine a witness via speakerphone).

Maintaining an indefinite pause on jury trials is a temporary response to a global pandemic, not a long-term solution. State courts handle roughly 106,000 trials per year, tens of thousands of which have already been suspended.{4} 4 See R.D. O’Brien, Is Anywhere Safe for a Jury Trial During the Covid-19 Pandemic? Try a School Gym, Wall St. J. (May 20, 2020), https://www.wsj.com/articles/is-anywhere-safe-for-a-jury-trial-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-try-a-school-gym-11589893201 (quoting Paula Hannaford-Agor, Director of the Center for Jury Studies at the National Center for State Courts). Likewise, many defendants facing criminal charges remain in custody, possibly endangering their right to a speedy trial and further risking exposure to the coronavirus.{5} 5 See M. Hendrickson, Man Awaiting Trial in Bar Fight 7th Cook County Jail Detainee to Die from Coronavirus Complications, Chi. Sun Times (May 6, 2020), https://chicago.suntimes.com/coronavirus/2020/5/6/21249680/arlington-heights-charged-bar-fight-cook-county-jail-detainee-die-coronavirus-related-illness. As stay-in-place orders ease and public spaces begin to reopen, jury trials will have to resume in some capacity.

When this occurs, safety from infection will rightly be at the forefront of everyone’s mind. Toward that end, judges have been developing innovative solutions to protect participants, especially jurors. Plans have included, inter alia, requiring masks, moving trial and deliberations to overlarge rooms to ensure social distancing, reducing the size of juror pools, and/or conducting proceedings via video conferencing platforms (e.g., Zoom or Microsoft Teams).{6} 6 See In the Matter of Authorizing Limitation of Court Operations During a Public Health Emergency and Transition to Resumption of Certain Operations, Administrative Order No. 2020-79 (Ariz. May 20, 2020), http://www.azcourts.gov/Portals/22/admorder/Orders20/2020-79.pdf?ver=2020-05-21-120117-320.

But while safety is imperative, the integrity of the jury system is also sacrosanct. Trials have operated roughly the same way since the founding of this country — and for very important reasons.{7} 7 See B. Murphy, Concerns About Infections Post-Pandemic Could Impact Future Jury Trials, Experts Say, Newsday (Apr. 19, 2020), https://www.newsday.com/news/health/coronavirus/coronavirus-jury-selection-long-island-1.43927317. Allowing criminal defendants to look their accusers in the eye, for instance, serves the truth-seeking function of cross-examination. Likewise, packed courtrooms open to the parties’ friends and families, as well as the press, promote systemic fairness. Limiting not only who may view the proceedings, but also how they are viewed, could fundamentally alter the judicial system.

As courts experiment with new procedures, they must take affirmative steps to protect defendants’ civil liberties — especially in the criminal context. As a threshold matter, while “trial by video” may be permissible in civil cases, it is wholly insufficient for criminal cases. Due process concerns would likely render a digital jury trial unconstitutional in the face of government prosecution. A long line of cases establishes defendants’ right under the Sixth Amendment to be physically present. Thus, video conferencing technology cannot replace criminal jury trials. What is needed, then, is a nuanced discussion about how best to resume in-person proceedings.

It would be naïve to dismiss the difficulties of restarting face-to-face jury trials. Participants must feel absolutely comfortable and safe in all aspects of the proceeding. Myriad issues must be considered — including voir dire, procedures for deliberation, effective advocacy, providing public access, speedy trial rights, and enforcing the basics of social distancing.{8} 8 See R. Emery & D. Cooper, COVID-19 Cannot Be the Death Knell for the American Jury Trial, Law.com (Apr. 20, 2020), https://www.law.com/newyorklawjournal/2020/04/20/covid-19-cannot-be-the-death-knell-for-the-american-jury-trial/.

At minimum, the pandemic will make it difficult to obtain a fair cross-section of the community, as required by the Sixth Amendment. In a recent study conducted by Dubin Research and Consulting (“DRC”), 74 percent of respondents indicated that they would be concerned about their health if called to serve as a juror and would be anxious about being in close proximity with other potential jurors. Given these concerns, high-risk (or simply risk-averse) individuals will undoubtedly self-select — refusing to respond to jury summonses for fear of infection. The judiciary must carefully consider these consequences and take active steps to mitigate them — before rushing to resume criminal trials. It is time to formulate a comprehensive plan for conducting criminal jury trials in a post-COVID-19 world.

This article proceeds in four sections. Section I describes how courts have addressed, or have proposed to address, the pandemic to date. Section II explains how conducting trials by video would violate criminal defendants’ core rights, based upon constitutional precedent and human psychology. Section III explores the reality of resuming in-person trials during a pandemic and identifies a host of obstacles that courts must first address. Finally, Section IV provides a set of core principles that should guide the operation of jury trials during these challenging times.

I. The Current State of Affairs

A. The Pandemic Halts Court Proceedings and Trials

Even as the pandemic was on the horizon in early March 2020, the courts proceeded with business as usual. Jurors, litigants, judges, clerks, and lawyers all packed into crowded elevators, hallways, and courtrooms. In New York City, all 33 of the city’s courthouses remained open, and people kept showing up for work.{9} 9 See N. Goldberg et al., Coronavirus Leaves Trail of Illness and Death in NYC Courthouses as Slow-to-Change System Struggles to Cope with Pandemic, N.Y. Daily News (May 25, 2020), https://www.nydailynews.com/coronavirus/ny-coronavirus-pandemic-unprepared-nyc-courts-20200526-fe2zknj7cbgutpjdn3vtfruiiq-story.html. And there were good reasons for doing so. Closing a court is not the same as closing a restaurant or a school. People’s liberties and constitutional rights would be at risk without a functioning judiciary to enforce them.

COVID-19 began to derail court proceedings in mid-March 2020. On March 16, a Manhattan judge declared a mistrial in the case of a doctor accused of sexual abuse after his defense attorney arrived at court with coronavirus-like symptoms.{10} 10 See Crane-Newman, supra. The judge initially tried to continue the proceedings by letting an attorney examine a witness via speakerphone from a different room in the courthouse, but ultimately announced, “Jurors, this case is over. I have to declare a mistrial. We need a fair trial. We need a lawyer who can represent his client.”{11} 11 Id. That same day, as COVID-19 cases began to skyrocket, New York’s Office of Court Administration issued an indefinite moratorium on trials and grand jury proceedings. But by then, judges, court personnel, jurors and litigants had contracted the virus, and sadly, in some cases it claimed their lives.{12} 12 See A. Denney, 3 New York Judges Died from Coronavirus, Almost 170 Court Workers Infected, N.Y. Post (Apr. 28, 2020), https://nypost.com/2020/04/28/coronavirus-in-ny-3-judges-die-almost-170-court-workers-infected/.

This same pattern repeated across the country, as lockdown orders were issued and cases were stopped in their tracks. For instance, the pandemic forced Los Angeles officials to close the county’s courthouses, halting the murder trial of Robert Durst (the heir to a New York real estate empire) after opening statements had already been given.{13} 13 See Associated Press, Robert Durst Murder Trial May Move to New California Court, N.Y. Times (May 24, 2020), https://apnews.com/59102accbed85361c8eecb41b43725a6; P. Vercammen & H. Silverman, Robert Durst Murder Trial Is Suspended Because of Coronavirus Concerns, CNN (Mar. 15, 2020), https://www.cnn.com/2020/03/15/us/california-jury-trials-suspended/index.html.

Now, as states begin to inch their way towards normalcy — by opening their cities in phases — courts have begun to reopen in parallel. For example, counties in rural Mississippi that have two or fewer reported deaths attributed to COVID-19 mailed jury summonses for trials beginning the week of May 18.{14} 14 See O’Brien, supra. Likewise, some courts in California, such as the Contra Costa County Superior Court, opened their doors on May 26.{15} 15 See M. Dolan, Some California Courts Start to Reopen as Coronavirus Restrictions Ease, L.A. Times (May 21, 2020), https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-05-21/some-california-courts-start-to-reopen-as-coronavirus-restrictions-ease. Even the Durst trial is expected to resume on July 27.{16} 16 However, the trial will be moved from the courthouse near Los Angeles International Airport to the larger Inglewood courthouse — to better promote social distancing.

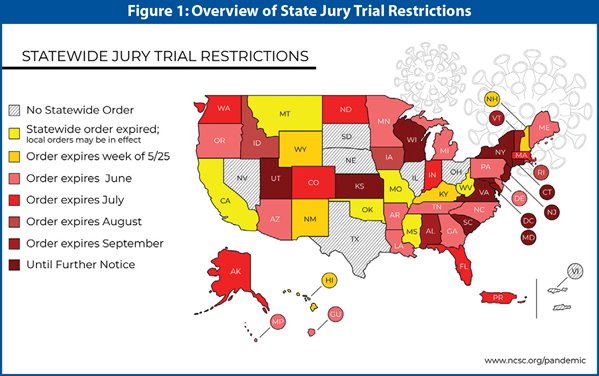

Figure 1 details the current status of each state’s restrictions on jury trials. It indicates that the majority of states will have lifted jury trial restrictions by July 2020.

The question on everybody’s mind, then, is how courts plan to contain the coronavirus. The following section explores the historic precedent for any such judicial response.

B. Historic Responses to Pandemics

The courts’ actions in response to this pandemic are not entirely without precedent. The 1918 influenza pandemic is the closest analog — it was the most severe pandemic in recent history. Nicknamed the “Spanish flu,” the influenza was caused by an H1N1 virus with genes of avian origin. At its worse, the Spanish flu infected 500 million people worldwide, which at the time was about a third of the Earth’s population. Although there is no universal consensus regarding where the virus originated, it spread worldwide from 1918-1919.{17} 17 See Center for Diseases Control and Prevention, 1918 Pandemic, https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-pandemic-h1n1.html (last accessed May 27, 2020).

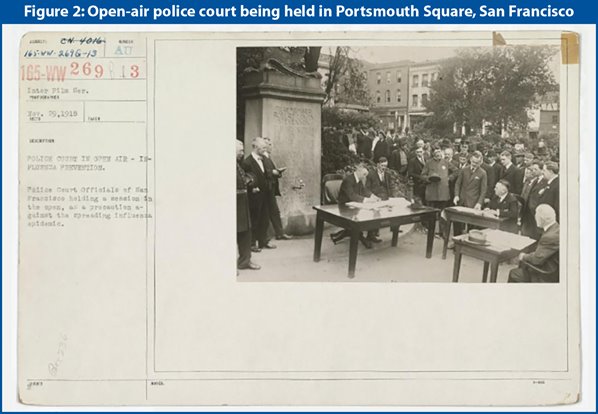

Not all U.S. courts appear to have closed in response to the 1918 influenza epidemic. One historian noted that in New York in October 1918, “New Yorkers caught spitting were usually rounded up and brought before courts in large numbers,” including over 130 men in a single day who were fined $1 for violating anti-spitting laws.{18} 18 See F. Aimone, The 1918 Influenza Epidemic in New York City: A Review of the Public Health Response (2010), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2862336/. Meanwhile, other courts appear to have introduced precautionary measures in response to the epidemic. It was believed that fresh air helped counteract the spread of the virus, so some court proceedings were held outside.{19} 19 See K. Canales, Photos Show the Precautions U.S. Cities Took to ‘Flatten the Curve’ During the 1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic, Business Insider (Apr. 13, 2020, https://www.businessinsider.com/spanish-flu-pandemic-1918-precautions-us-cities-2020-4. Figure 2, an image in the National Archives, shows one such assembly in San Francisco.{20} 20 National Archives Catalogue, Medical Department - Influenza Epidemic 1918 - Police Court in open air - influenza prevention. Police Court Officials of San Francisco holding a session in the open, as a precaution against the spreading influenza epidemic, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/45499315.

The Supreme Court, on the other hand, postponed scheduled arguments for October 1918 in response to the Spanish flu epidemic for about a month.{21} 21 See M. Walsh, Outbreaks of Disease Have Shuttered the Supreme Court Going Back More Than 2 Centuries, ABA J. (Mar. 19, 2020), https://www.abajournal.com/web/article/outbreaks-have-shuttered-the-supreme-court-going-back-more-than-two-centuries. The Court also restricted who could be admitted into the courthouse, denying entry to all persons but lawyers.{22} 22 See C. Cushman, Epidemics and the Supreme Court, supremecourthistory.org, https://supremecourthistory.org/history-of-the-court/Epidemics%20and%20the%20Supreme%20Court/.

The Court had previously shortened its argument calendars in August 1793 and August 1798 in response to yellow fever outbreaks.{23} 23 See id. During the 1798 epidemic, other courts continued to hold arguments but were moved to courthouses outside of the epicenters of the outbreaks.{24} 24 See id. This included the Philadelphia circuit court, which held session in Norristown, north of the city.

While precautionary measures and court closures have historical authority, many of the constitutional rights afforded to defendants today had not yet been defined by the Supreme Court. One historian noted that the Bill of Rights was only beginning to be leveraged in the 1920s, having spent nearly 130 years in relative obscurity, rarely cited by the Supreme Court.{25} 25 See United States Courts, Now Cherished, Bill of Rights Spent a Century in Obscurity, USCourts.gov, (Dec. 12, 2019), https://www.uscourts.gov/news/2019/12/12/now-cherished-bill-rights-spent-century-obscurity. In fact, in 1918, the Supreme Court had only recently approved of “drawing of a jury from a part of the district, rather than from the entire district.”{26} 26 Ruthenberg v. United States, 245 U.S. 480, 481 (1918).

Thus, the modern judiciary had little precedent to guide its response to COVID-19. The next section outlines how courts in various jurisdictions have chosen to proceed.

C. How Courts Have Responded to the Pandemic to Date

i. Telephonic Hearings

The inability to resume court proceedings in person forced courts across the nation to embrace technology in ways they never had before. The leading example is the U.S. Supreme Court, which broke from tradition by conducting arguments via conference call.{27} 27 See A. Liptak, Virus Pushes a Staid Supreme Court Into  Revolutionary Changes, N.Y. Times (May 3, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/03/us/politics/supreme-court-coronavirus.html. Within the federal court system more broadly, teleconference hearings have been encouraged in some jurisdictions (e.g., Eastern District of New York, Southern District of California, and Northern District of Illinois), while outright required in others (e.g., Eastern District of Pennsylvania, District of Maine, and Northern District of Florida).

Revolutionary Changes, N.Y. Times (May 3, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/03/us/politics/supreme-court-coronavirus.html. Within the federal court system more broadly, teleconference hearings have been encouraged in some jurisdictions (e.g., Eastern District of New York, Southern District of California, and Northern District of Illinois), while outright required in others (e.g., Eastern District of Pennsylvania, District of Maine, and Northern District of Florida).

ii. Videoconference Hearings

Videoconferencing platforms have been adopted in an effort to restart the justice system. Most recently, in the U.S. District Court for the District of Massachusetts, Judge Nathaniel M. Gorton held a remote video proceeding during which actress Lori Loughlin and her husband, Mossimo Giannulli, pled guilty in the notorious college admissions case.{28} 28 See C. Villani, Lori Loughlin, Husband Plead Guilty in ‘Varsity Blues,’ Law360 (May 22, 2020), https://www.law360.com/california/articles/1276185. However, the hearing, which was conducted over Zoom, was not without hiccups. The judge had to remind speakers to mute or unmute themselves.

With respect to proceedings necessitating jurors, certain courts have also begun launching pilot programs to determine whether technology can meet their needs. For example, on May 14, New Jersey launched a pilot program to hold virtual grand jury proceedings via Zoom in Bergen and Mercer counties.{29} 29 See News Release, Judiciary Launches Virtual Grand Jury Pilot Program, New Jersey Courts (May 14, 2020), https://njcourts.gov/pressrel/2020/pr051420a.pdf. Similarly, on May 22, Florida Chief Justice Charles Canady ordered the creation of a pilot program for civil jury trials via remote technology.{30} 30 See D. Atkins, Fla. Courts Launch Remote Civil Jury Trial Pilot Program, Law360 (May 22, 2020), https://www.law360.com/articles/1276219/fla-courts-launch-remote-civil-jury-trial-pilot-program.

D. How Courts Plan to Resume Jury Trials

Federal and state courts that have announced plans to resume jury trials generally fall into two categories. The first approach virtualizes the entire trial experience. The second approach favors in-person jury trials — but with enhanced safeguards intended to contain the virus. A representative sample of each approach is presented below, based on current information.

i. A Virtual Trial — Texas

Texas has emerged as a leader in embracing remote video technology by being the first state to conduct a civil bench trial and jury trial on the platform. On April 22, Harris County Judge Beau Miller held a one-day bench trial in an attorney fee dispute case.{31} 31 See D. Siegal, Texas Court Pioneers Trial by Zoom in Atty Fee Dispute, Law360 (April 22, 2020), https://www.law360.com/articles/1265459/texas-court-pioneers-trial-by-zoom-in-atty-fee-dispute. The proceeding was livestreamed on the court’s website. Judge Miller noted that there had been more than 2,000 virtual audience members throughout portions of the day.

Less than a month later, the state charted new territory by using remote video to conduct a civil jury trial.{32} 32 See K. Pohlman, Texas Court Holds First Jury Trial Via Zoom in Insurance Feud, Law360 (May 18, 2020), https://www.law360.com/articles/1274097/texas-court-holds-first-jury-trial-via-zoom-in-insurance-feud. A Collin County summary jury trial kicked off with two state court judges and three attorneys vetting 25 prospective jurors.{33} 33 The summary jury trial was part of an alternative dispute resolution process. The presiding judge instructed jurors that, despite the use of Zoom, they were still in court and could not Google information or use their phones. He also warned jurors that they might need to ask family members to leave the room.

For voir dire, the panel was divided into two groups. The attorneys questioned 12 jurors, while the remaining 13 jurors were placed in a virtual break-out room. During this process, the attorneys asked prospective jurors to raise their hands to show where they stood on relevant issues. They were then called upon to discuss their answers further. Once the voir dire process was complete, which took 45 minutes, the judge asked the parties to “approach the bench.” In the world of Zoom, this meant that the judge created a new break-out room for litigants to communicate without the jurors hearing. Once they returned to the main Zoom meeting, the trial proceeded with the 12 jurors on the panel. The trial’s only noted hiccup was when a juror wandered offscreen during a break and could not hear the judge calling him back.{34} 34 See A. Morris, Juror Walks Off to Take Phone Call as Texas Tests First Jury Trial Via Zoom, Law.com (May 18, 2020), https://www.law.com/texaslawyer/2020/05/18/juror-walks-off-to-take-phone-call-as-texas-tests-first-jury-trial-via-zoom/.

The virtual interface mirrors the configuration depicted in Figure 3, with all potential jurors visible simultaneously alongside the litigants, attorneys, and presiding judge.

ii. A (Modified) In-Person Trial — New York

The Southern District of New York is undertaking the necessary transformation to resume in-person jury trials, although no reopening date has been announced. Chief Judge Collen McMahon announced that plexiglass will be the norm — courtrooms will be refurbished so that witnesses testify behind a clear plastic barrier. Likewise, jurors will be seated further apart in the jury box in accordance with social distancing restrictions.{35} 35 See P. Brush, The New Normal in SDNY Will Include ‘Lots of Plexiglass,’ Law360 (May 20, 2020), https://www.law360.com/articles/1275480.

Social distancing will also be enforced in the security line with distancing indicators on the floor and limits on the number of people allowed in the elevators. District Executive Edward Friedland added that there will be limits to the number of lawyers in the courtroom wells and who can observe.{36} 36 See id. In addition to masking and following hygiene protocols, court personnel will be screened for the virus and asked to self-report symptoms.{37} 37 See id.

Thus far, the court has not indicated whether jury deliberations will be conducted in traditionally designated areas, what protocols will be enacted around jurors handling evidence, or if the number of people that can observe the proceeding will be limited (e.g., potentially barring the family of the defendants from attending the trial). While the Southern District of New York has not announced whether it will adopt a videoconferencing platform for virtual trials, prior to New York City’s PAUSE order being issued, District Judge Alison Nathan took the unprecedented step of allowing an ill juror to deliberate via FaceTime.{38} 38 See S. Bishop, SDNY Judge Lets Sick Juror Deliberate Via Videoconference, Law360 (March 16, 2020), https://www.law360.com/articles/1253726/sdny-judge-lets-sick-juror-deliberate-via-videoconference. Judge Nathan noted, “[W]e are in extraordinary circumstances and given the situation it is appropriate to proceed thusly.”{39} 39 Id.

With respect to the New York State courts, Chief Judge Janet DiFiore described several safety measures that  will be implemented. These include the mandatory use of masks by all persons entering the courthouse, social distancing protocols, strict cleaning and sanitizing standards, and the installation of plexiglass partitions in strategic courthouse locations.{40} 40 See Transcript of Message From New York Chief Judge DiFiore (May 25, 2020), https://www.nycourts.gov/whatsnew/pdf/May25MessagefromCJ.pdf.

will be implemented. These include the mandatory use of masks by all persons entering the courthouse, social distancing protocols, strict cleaning and sanitizing standards, and the installation of plexiglass partitions in strategic courthouse locations.{40} 40 See Transcript of Message From New York Chief Judge DiFiore (May 25, 2020), https://www.nycourts.gov/whatsnew/pdf/May25MessagefromCJ.pdf.

iii. Other Approaches

A handful of courts in the country recently resumed in-person operations. For example, on May 26, California’s Contra Costa County Superior Court reopened all locations and resumed jury trials with precautionary measures.{41} 41 See Dolan, supra. These include mandated face coverings at all times while inside the courthouse, taking the temperature of anyone entering the court and denying entry to those who have a temperature of 100 degrees or higher, admitting no more than 50 prospective jurors in the assembly room, and excusing potential jurors exhibiting COVID-19 symptoms or those who are high-risk (e.g., over 60 years of age or immunocompromised).{42} 42 See Superior Court of California, County of Contra Costa, Urgent Release: Court Reopening (May 13, 2020). https://www.cc-courts.org/general/docs/PressRelease-COVID19-05-13-20.pdf. The court’s press release also states, “No Nonessential Parties. Due to social distancing limitations, individuals who are not essential to Court matters should not accompany parties to Court for any matter or case type.”{43} 43 Id. (emphasis in original). The press release makes no mention as to whether courtroom proceedings will be broadcast to the public.{44} 44 In the Eastern District of Texas, Chief Judge Gilstrap told Law360 that the court anticipates beginning jury trials at the start of June, with health measures in place. This includes -- endnote

California’s Monterey Superior Court, which will open in June, announced on its website that “fewer trials will be in session at any one time to reduce the number of people in the courthouse.”{45} 45 CAPortal, County of Monterey, Check Jury Duty Status, https://portal.monterey.courts.ca.gov/jury (last accessed May 27, 2020). With respect to jury deliberations, the court announced that deliberations will occur in the courtroom rather than in the traditional jury deliberation room. In order to adhere to social distancing guidelines, the court also announced that “members of the public may be precluded from attending jury trials in person,” while adding that public call-in lines have been created for each courtroom so that members of the public can call in and listen to trials.

Other jurisdictions have found that they need to step out of the courthouse in order to safely conduct a jury trial. For example, in northwestern Montana, a school gym will be transformed into a courtroom, as it is the only place in the county where 100 prospective jurors can gather while adhering to social distancing guidelines.{46} 46 See O’Brien, supra. This will be the home to a domestic-assault trial set to begin on June 9. Whether this venue will still be used when school resumes remains to seen.

The Supreme Court of Arizona even issued an order limiting peremptory challenges to two per side in order to minimize the size of the jury pool. Specifically, it modified procedural rules “to afford litigants only two peremptory strikes for potential jurors per side in all civil and felony cases tried in the superior court, and one peremptory strike per side in all misdemeanor cases.”{47} 47 Administrative Order No. 2020-79, In re Matter of: Authorizing the Limitation of Court Operations During a Public Health Emergency and Transition to Resumption of Certain Operations (Ariz. May 20, 2020), http://www.azcourts.gov/Portals/22/admorder/Orders20/2020-79.pdf?ver=2020-05-21-120117-320. By limiting the number of jurors released on peremptory grounds, the court hopes “to reduce the number of citizens summoned to jury duty” and, therefore, the risk of infection.{ 48} 48 Id.

Most recently, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas announced plans to resume in-person jury trials, including trials against criminal defendants. U.S. District Judge James Wesley “Wes” Hendrix scheduled a jury trial in United States v. Santos, which is set to begin on June 15, 2020, in the Abilene courthouse.{49} 49 A. Morris, Jury Trials Are Back in Texas. Here’s What You Should Know, Law.com (Jun. 8, 2020), https://www.law.com/texaslawyer/2020/06/08/jury-trials-are-back-in-texas-heres-what-you-should-know/. The case involves a felony charge for attempted enticement of a minor.{50} 50 Id. In anticipation of trial, Judge Hendrix issued a Notice of Trial Procedures, which enumerates various safety measures intended to mitigate COVID-19. Among other things, the court will take jurors’ temperatures, disinfect common spaces, and ensure social distancing.{51} 51 United States v. Santos, Case No. 1:19-CR-107-H-BU, slip op. (N.D. Tex. Jun. 8, 2020), Dkt. No. 57 at 1. Regarding the latter protocol, the court will conduct voir dire in the Lubbock County Central Jury Pool building because it is large enough to permit the jury panel to remain at least six feet apart at all times.{52} 52 Id. Likewise, jury deliberation will “occur in a large room to permit social distancing.”{53} 53 Id. The court will also require participants, including witnesses, to wear clear plastic face shields. Finally, while Judge Hendrix intends to limit seating in the physical courtroom, a live audiovisual feed will be provided — both in an overflow room and through remote means.{54} 54 Id. at 2.

Thus, there exists a wide range of responses to the pandemic, mirroring the relative impact of COVID-19 in each jurisdiction and the local communities’ resulting attitudes. But despite these numerous approaches, one thing is clear. While virtual trials may be sufficient to handle civil cases, they cannot substitute for in-person proceedings when applied to criminal defendants. The following section explores these fatal constitutional shortcomings.

II. Virtual Criminal Trials Cannot Overcome Key Constitutional Hurdles

To keep the wheels of justice turning, most courts have been conducting a host of proceedings by video or teleconference, including arraignments, guilty pleas, and sentencing, with the consent of the defendant. This is a significant change for the legal system, where long-standing rights entitle defendants to be charged, tried, and judged by people they can look in the eye.

While no court has yet conducted a full jury trial remotely, there have been clear moves in that direction. For instance, in a statewide order staying all jury trials, Chief Justice Tani G. Cantil-Sakauye of California noted, “Courts may conduct such a trial at an earlier date, upon a finding of good cause shown or through the use of remote technology, when appropriate.”{55} 55 See Judicial Council of California, Statewide Order by Hon. Tani G. Cantil-Sakauye (Mar. 23, 2020), http://www.glenncourt.ca.gov/general-info/documents/Statewide%20Order%20by%20the%20Chief%20Justice-Chair%20of%20the%20Judicial%20Council%20(3-23-2020).pdf. Likewise, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York recently began allowing grand jurors to convene and deliberate via video conference.{56} 56 See P. Brush, Grand Jurors in SDNY Get Video Option Amid Virus Outbreak, Law360.com, https://www.law360.com/articles/1255774/grand-jurors-in-sdny-get-video-option-amid-virus-outbreak.

However, while “jury trial by video” may be permissible in the civil context, it raises grave constitutional concerns when applied to criminal proceedings. The arguments against remote testimony in criminal trials are plentiful. Remote testimony may violate defendant’s right to be confronted with the evidence against him or her because the testimony is not “face-to-face.” Remote testimony cannot ensure truthfulness to the same extent as requiring the witness to testify live before the defendant. Remote testimony limits the information available to defendants when assessing juror bias. And remote testimony, as opposed to live testimony, does not provide the court and jury with the same opportunity as does live testimony to assess the demeanor and truthfulness of the witness. Each of these issues is addressed in turn below.

A. Criminal Defendants Have a Fundamental Right to Physically Face Their Accuser

The Sixth Amendment’s Confrontation Clause assures the right of an accused “to be confronted with the  witnesses against him.”{57} 57 U.S. Const. amend. VI. The U.S. Supreme Court has declared that face-to-face confrontation forms “the core of the values furthered by the Confrontation Clause.”{58} 58 Coy v. Iowa, 487 U.S. 1012, 1017 (1988) (citing California v. Green, 399 U.S. 149, 157 (1970)). This core value serves dual purposes. First, facing one’s accusers deters false accusations, as it is far more difficult to lie when looking directly upon the accused.{59} 59 See id. at 1019-20. Second, face-to-face confrontation enables jurors to “examine the demeanor of the witness as the witness accuses the defendant, as well as the demeanor of the defendant as he hears the accusations. …”{60} 60 See C.A. Chase, The Five Faces of the Confrontation Clause, 40 Hous. L. Rev. 1003, 1011 (2003). This, in turn, enables jurors to more properly assess credibility.{61} 61 See id.

witnesses against him.”{57} 57 U.S. Const. amend. VI. The U.S. Supreme Court has declared that face-to-face confrontation forms “the core of the values furthered by the Confrontation Clause.”{58} 58 Coy v. Iowa, 487 U.S. 1012, 1017 (1988) (citing California v. Green, 399 U.S. 149, 157 (1970)). This core value serves dual purposes. First, facing one’s accusers deters false accusations, as it is far more difficult to lie when looking directly upon the accused.{59} 59 See id. at 1019-20. Second, face-to-face confrontation enables jurors to “examine the demeanor of the witness as the witness accuses the defendant, as well as the demeanor of the defendant as he hears the accusations. …”{60} 60 See C.A. Chase, The Five Faces of the Confrontation Clause, 40 Hous. L. Rev. 1003, 1011 (2003). This, in turn, enables jurors to more properly assess credibility.{61} 61 See id.

Whether the Confrontation Clause forbids virtual trials represents new terrain. No authority exists — in the federal Constitution or most state analogues — that outright prohibits the practice. On the other hand, no authority explicitly permits them, either.{62} 62 See M. Pressman, Bench Trial by Videoconference, Civil Jury Project of NYU Law School (May. 6, 2020), https://civiljuryproject.law.nyu.edu/commentary/. Thus, in assessing whether an appellate court would affirm a verdict arising out of a remote video proceeding, we must consult analogous precedents involving videoconferencing.

i. The Supreme Court’s Guiding Principles

The Supreme Court encountered the issue of live, audiovisual testimony on two occasions. In Coy v. Iowa, the Supreme Court reversed a sexual-assault conviction, concluding that the lower court’s decision to permit two child witnesses to testify behind a large screen where they could not see the defendant violated the defendant’s confrontation rights. In reaching this conclusion, Justice Scalia, writing for the majority, stated: “We have never doubted … that the Confrontation Clause guarantees the defendant a face-to-face meeting with witnesses appearing before the trier of fact.”{63} 63 Coy, 487 U.S. at 1016. He further stated that “the irreducible literal meaning of the Clause” is “[the] right to meet face to face all those who appear and give evidence at trial.”{64} 64 Id. at 1020–21. According to Scalia, “there is something deep in human nature that regards face-to-face confrontation between accused and accuser as ‘essential to a fair trial in a criminal prosecution,’”{65} 65 Id. at 1017 (citing Pointer v. Texas, 380 U.S. 400, 404 (1965)). in that a witness “may feel quite differently when he has to repeat his story looking at the man whom he will harm greatly by distorting or mistaking the facts.”{66} 66 Id. at 1019 (citation omitted). He further added, “It is always more difficult to tell a lie about a person ‘to his face’ than ‘behind his back.’ In the former [case], even if the lie is told, it will often be told less convincingly.”{67} 67 Id.

Despite this strong language, however, the right to confrontation is not absolute.{68} 68 In Coy, four Justices wrote or joined in separate concurring or dissenting opinions to emphasize that any right conferred by the Confrontation Clause requiring the witness to physically face the defendant was not absolute. Id. at 1024. In Maryland v. Craig,{69} 69 Maryland v. Craig, 497 U.S. 836 (1990) (emphasis in original). the Court held that the Confrontation Clause does not prohibit a state from using one-way closed-circuit television to capture testimony of a child witness in a child abuse case — even where the child cannot view the defendant while testifying.{70} 70 See id. at 855. The Court declared that, “[a]lthough face-to-face confrontation forms ‘the core of the values furthered by the Confrontation Clause,’ … it is not the sine qua non of the confrontation right.”{71} 71 Id. at 847 (citations omitted). Rather, the Court found that the Confrontation Clause “reflects a preference for face-to-face confrontation at trial,” which “must occasionally give way to considerations of public policy and the necessities of the case.”{72} 72 Id. at 848-849 (internal citations omitted).

Applying these principles, Craig created a two-part test for determining whether an exception to the Confrontation Clause’s face-to-face requirement is warranted: “[A] defendant’s right to confront accusatory witnesses may be satisfied absent a physical, face-to-face confrontation at trial only where [1] denial of such confrontation is necessary to further an important public policy and [2] the reliability of the testimony is otherwise assured.”{73} 73 Id. at 850 (emphasis added). With respect to the first prong, Craig added the additional requirement of a “case-specific” finding of necessity.{74} 74 Id. at 855-56 (emphasis added).

Thus, the Supreme Court indicated a willingness to retreat from a literal application of the Sixth Amendment — but only in “narrow circumstances” and on a “case-specific” basis.{75} 75 Id. According to Justice O’Connor, “in certain narrow circumstances, ‘competing interests … may warrant dispensing with confrontation at trial.’” Id. at 848.

ii. A Split Amongst the Circuit Courts

Lower courts do not agree on how to apply the foregoing precedent. Some federal courts view the Confrontation Clause as guaranteeing the defendant a general right to contemporaneously cross-examine adverse witnesses.{76} 76 See, e.g., M.C. McAllister, Two-Way Video Trial Testimony and the Confrontation Clause: Fashioning a Better Craig Test in Light of Crawford, 34 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 836, 841–42 (2007). Other courts provide a more specific right to examine witnesses face-to-face in the defendants’ physical presence.{77} 77 See, e.g., Yates, 438 F.3d 1307, 1312–14 (11th Cir. 2006) (en banc) (holding that the accused has a right to physical face-to-face confrontation). Whether a court is inclined to permit remote prosecution-witness testimony depends, in part, on the level of significance it attaches to the face-to-face component of the Sixth Amendment.

For instance, in Gigante,{78} 78 United States v. Gigante, 166 F.3d 75, 79–81 (2d Cir. 1999). the Second Circuit found no violation of a defendant’s Confrontation Clause rights when the trial court permitted a mob informant dying of inoperable cancer to testify from a remote location by two-way, live videoconferencing technology.{79} 79 See id. at 79–81. While acknowledging that in-court testimony may have “intangible elements ... that are reduced or even eliminated by remote testimony,” the court rejected the notion that the defendant was entitled to face his accuser “in the same room.”{80} 80 Id. at 80. Instead, the Court held that the two-way videoconferencing procedure “preserved the face-to-face confrontation celebrated by Coy.”{81} 81 Id. at 81.

The Eleventh Circuit came to the opposite conclusion in Yates. There, the trial court’s decision to allow two Australian nationals to testify remotely from Australia against two defendants in a criminal trial in Alabama violated the defendants’ Confrontation Clause rights, notwithstanding that the witnesses were beyond the government’s subpoena powers.{82} 82 See Yates, 438 F.3d at 1309–10. Applying the Craig test, the court found that confrontation was not “necessary.” Specifically, it found that, although “presenting the fact-finder with crucial evidence is, of course, an important public policy, … the prosecutor’s need for the videoconference testimony to make a case and to expeditiously resolve it are not the type of public policies that are important enough to outweigh the defendants’ rights, to confront their accusers face-to-face.”{83} 83 Id. at 1316. The court noted that a Rule 15 deposition in Australia with all necessary parties was a potential alternative, which would have preserved the defendants’ confrontation rights.{84} 84 See id.

iii. Application to the Coronavirus Pandemic

Precedent suggests that traditional constitutional rights (such as confrontation) can be satisfied or modified if video conferencing satisfies other sufficiently important interests. Of course, existing confrontation clause jurisprudence did not consider the scope of a national emergency like COVID-19. The challenges posed by the virus — i.e., the continued operation of the judiciary during a time when in-person jury trials could be deadly — are certainly extreme. Keeping participants alive is indeed a public policy of prime importance.

But Craig requires more. It requires that any use of remote testimony be individually considered on a “case-specific” basis. Categorical assessments are simply not permitted. Any attempt by a court to impose a blanket rule, e.g., one which permits virtual testimony in all cases during the pandemic, would run afoul of this constitutional principle.

This requirement is no afterthought. The Supreme Court has rejected attempts to deprive defendants of face-to-face confrontation based on such blanket rules. For instance, in 2002, the Court considered a proposed  amendment to Rule 26 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure that would have explicitly permitted video testimony in “exceptional circumstances.”{85} 85 Yates, 438 F.3d at 1314; see also Proposed Amendments to the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure (Apr. 29, 2002) (appendix to statement of Breyer, J.) [hereinafter Proposed Rule 26(b)]. Under Proposed Rule 26(b), federal courts would have been able to authorize two-way, live videoconferencing technology from a remote location in criminal cases “in the interest of justice” when the requesting party established (1) “exceptional circumstances for such transmission,” (2) the transmission used “appropriate safeguards,” and (3) the witness was otherwise “unavailable” to attend the trial in person.{86} 86 Proposed Rule 26(b) at 7. The Court declined to adopt the proposal, however, for failure to “limit the use of testimony via video transmission to instances where there has been a case-specific finding that it is necessary to further an important public policy.” The majority appeared to consider a separate statement filed by Justice Scalia, wherein he indicated that the proposed amendment was of “dubious validity under the Confrontation Clause.”{87} 87 Yates, 438 F.3d at 1314–15. He observed that “[v]irtual confrontation might be sufficient to protect virtual constitutional rights. I doubt whether it is sufficient to protect real ones.”{88} 88 See Amendments to Rule 26(b) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, 207 F.R.D. 89, 94 (2002) (statement of Scalia, J.). A court order that permits remote video trials during a pandemic — while well-meaning — would fail to meet this high bar.

amendment to Rule 26 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure that would have explicitly permitted video testimony in “exceptional circumstances.”{85} 85 Yates, 438 F.3d at 1314; see also Proposed Amendments to the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure (Apr. 29, 2002) (appendix to statement of Breyer, J.) [hereinafter Proposed Rule 26(b)]. Under Proposed Rule 26(b), federal courts would have been able to authorize two-way, live videoconferencing technology from a remote location in criminal cases “in the interest of justice” when the requesting party established (1) “exceptional circumstances for such transmission,” (2) the transmission used “appropriate safeguards,” and (3) the witness was otherwise “unavailable” to attend the trial in person.{86} 86 Proposed Rule 26(b) at 7. The Court declined to adopt the proposal, however, for failure to “limit the use of testimony via video transmission to instances where there has been a case-specific finding that it is necessary to further an important public policy.” The majority appeared to consider a separate statement filed by Justice Scalia, wherein he indicated that the proposed amendment was of “dubious validity under the Confrontation Clause.”{87} 87 Yates, 438 F.3d at 1314–15. He observed that “[v]irtual confrontation might be sufficient to protect virtual constitutional rights. I doubt whether it is sufficient to protect real ones.”{88} 88 See Amendments to Rule 26(b) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, 207 F.R.D. 89, 94 (2002) (statement of Scalia, J.). A court order that permits remote video trials during a pandemic — while well-meaning — would fail to meet this high bar.

It must also be noted that the diversity of state constitutions means that any analogy to the Confrontation Clause will be inapplicable in some states — especially states whose highest courts have disagreed with Craig. For instance, the Illinois Supreme Court held, “[W]e conclude that the confrontation clause of the Illinois Constitution provides that a defendant is entitled to a face-to-face confrontation with a witness.”{89} 89 People v. Fitzpatrick, 158 Ill. 2d 360, 365 (1994); see also Commonwealth v. Bergstrom, 524 N.E.2d 366, 371-72 (1988) (“The plain meaning of assuring a defendant the right ‘to meet the witnesses against him face to face’ is that the accused shall not be tried without the presence … of both himself and the witnesses testifying against him.”). Virtual trials are plainly unconstitutional in such states on separate grounds, irrespective of Supreme Court precedent.

iv. Case Law on Unavailability Provides Additional Guidance

Case law concerning the treatment of sick witnesses provides further guidance. In very limited circumstances, prosecution witnesses have also been permitted to testify remotely due to severe illness. No court has permitted virtual testimony based on the prospect that a witness will become ill in the future.

To the contrary, courts typically squabble over the extent and duration of the illness necessary to evidence unavailability. For example, in Gigante, Peter Savino, “a former associate of the Genovese family,” was “in the final stages of an inoperable, fatal cancer, and was under medical supervision at an undisclosed location.”{90} 90 Gigante, 166 F.3d 75 at 79. After hearing testimony from physicians, the trial judge found that it would be medically unsafe for the witness to travel to New York for the trial, and allowed him to testify via two-way video.{91} 91 Id. at 79-80.

Similarly, in Horn v. Quarterman,{92} 92 Horn v. Quarterman, 508 F.3d 306, 313–20 (5th Cir. 2007). the Fifth Circuit allowed remote two-way testimony by a witness who was terminally ill, hospitalized for liver cancer, and not expected to improve. The Court found that, “after discussing Birk’s condition with Birk’s doctor, that use of the unorthodox procedure was necessary, and emphasized that other aspects of the Confrontation Clause were maintained.” On that basis, it found that the “state court records reflect that a case-specific finding of necessity was made. …”{93} 93 See also Bush v. State, 193 P.3d 203, 215, 214 (Wyo. 2008) (two-way testimony allowed when the witness suffered from a medical condition that was “serious and severe and not temporary”; the witness suffered from -- endnote

Nobody seriously disputes that witnesses suffering from the coronavirus and confined to a hospital may be permitted to testify remotely. But current proposals to conduct virtual trials make an additional logical leap. They permit remote testimony for witnesses that are not yet sick — but merely risk becoming sick if they provide in-court testimony. Such speculation is insufficient to establish unavailability.

B. Defendants Have a Right to Participate in Their Own Defense

A criminal defendant’s right to be present at his trial is “[o]ne of the most basic of the rights guaranteed by the Confrontation Clause.”{94} 94 Illinois v. Allen, 397 U.S. 337, 338 (1970) (citing Lewis v. United States, 146 U.S. 370 (1892)) (the defendant has the right to be present during all stages of a trial). This right is closely tied to an accused’s right to confront witnesses as he must necessarily be in the courtroom to obtain the face-to-face confrontation of the evidence against him contemplated by the Sixth Amendment.{95} 95 Coy, 487 U.S. at 1015 (holding that the Sixth Amendment right of a criminal defendant “to be confronted with the witnesses against him” guarantees a face-to-face encounter between a witness and the accused). The defendant’s right is also protected, in some situations, by the Due Process Clause. The Supreme Court has explained that a defendant has a due process right to be present at a proceeding “whenever his presence has a relation, reasonably substantial, to the fulness [sic] of his opportunity to defend against the charge. … [T]he presence of a defendant is a condition of due process to the extent that a fair and just hearing would be thwarted by his absence, and to that extent only.”{96} 96 United States v. Gagnon, 470 U.S. 522 (1985) (citing Snyder v. Mass., 291 U. S. 97 (1934)). Additionally, the defendant’s presence is also often mandated by court rule. For instance, Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 43 sets forth the circumstances in which the defendant’s presence is required, not required, and can be waived.{97} 97 New York Criminal Procedure Law Section 340.50 similarly proscribes that “a defendant must be personally present during the trial” unless certain exceptions are met.

Remote video trials, where the court conducts the proceedings over an online webinar, raise several issues for a defendant’s right to be present.

i. The Right to Be Present, Like the Right to Confront, Does Not Meet the Craig Bar

First, there is the question of whether appearing by video on a webinar would qualify as being present within the meaning of the Sixth Amendment. Though Justice Scalia, among others, argued that testimony via videoconference “improperly substitute[ed] ‘virtual confrontation’ for the real thing required by the Confrontation Clause in a criminal trial,”{98} 98 R.L. Marcus, E-Discovery & Beyond: Toward Brave New World or 1984? 25 Rev. Litig. 633 at 676 (2006). the Craig decision again clarified that the Confrontation Clause does not guarantee criminal defendants an absolute right to a face-to-face meeting with the witnesses against them.{99} 99 Craig, 497 U.S. at 849. Thus, a remote video trial, in the absence of case-specific findings of necessity, would likely violate a defendant’s rights to be present for the same reasons as his or her confrontation rights.

ii. Virtual Trials May Impair Defendants’ Ability to Detect Juror Bias

A defendant’s right to be present at trial extends to the empaneling of the jury.{100} 100 See Pointer v. United States, 151 U.S. 396, 408 (1894). For instance, Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 43(a) requires that “witness testimony must be taken in open court,” absent “compelling circumstances” and “appropriate safeguards.”{101} 101 Fed. R. Civ. P. 43(a). This rule has been interpreted to “afford[] a defendant the right to be present during jury empanelment.”{102} 102 United States v. Gordon, 829 F.2d 119, 123 (D.C. Cir. 1987) (stating that Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 43(a), affording a defendant the right to be present during jury empanelment, “embodies the protections afforded by the Sixth Amendment Confrontation Clause, the due process guarantee of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments, and the common law right of presence.”).

Other jurisdictions adhere to this basic rule.{103} 103 See, e.g., Hager v. United States, 79 A.3d 296, 302-03 (D.C. 2013) (“[T]he right extends not only to the defendant’s ability to hear the responses that jurors give, but also to reasonably view their demeanor during those responses in order to assess their various qualities as jurors and make decisions about whether to exercise challenges. Otherwise, the defendant’s right to “observe” voir dire would be rendered meaningless,” and noting that “it is reasonable for us to assume that from Davis’s position while sitting at counsel table the jurors were turned away from him and his primary view during voir dire would have been of their backs.”). The case of People v. Antommarchi is illustrative.{104} 104 People v. Antommarchi, 80 N.Y.2d 247, 250 (N.Y. 1992). During voir dire, the judge questioned several prospective jurors at the bench regarding personal matters they did not wish to share in open court. These sidebar conferences took place while the defendant remained a few feet away. The defendant appealed his conviction to the New York Court of Appeals, claiming that his absence from the sidebar conferences deprived him of his right to be present at every material stage of trial. The New York Court of Appeals agreed and reversed his conviction. The court reasoned that:

Defendants are entitled to hear questions intended to search out a prospective juror’s bias, hostility or predisposition to believe or discredit the testimony of potential witnesses and the venire person’s answers so that they have the opportunity to assess the juror’s “facial expressions, demeanor and other subliminal responses.”{105} 105 Id. (internal citations omitted).

The prospect of a virtual voir dire, therefore, raises a slew of concerns. The ability to get an up-close view of witnesses on video chat might help jurors analyze facial expressions more closely. Or it could cut the opposite way, inflaming existing prejudices. Even with the advent of high-definition videoconferencing software, participants may be less likely to detect the nuances of body language and facial expressions when testimony is transmitted remotely. This will almost certainly make it more difficult for defendants to identify juror bias and impartiality. In addition, it is unclear whether remote selection would emphasize one-on-one, face-to-face communication — only showing one potential juror at a time. Litigants want to be able to see that panel as a whole in order to observe the reaction of other jurors to whom a particular question is not pending.

Indeed, even those courts planning to conduct in-person voir dire face challenges. For instance, it remains to be seen how the installation of glass dividers between jurors, such as proposed in the Southern District of New York, would impact the defendant’s view of each juror. Any restriction on the defendant’s ability to observe potential jurors would infringe upon his or her right to be present.

iii. Logistical Challenges May Further Prejudice a Criminal Defendant

During a remote video proceeding, how will judges ensure that the defendant has access to his or her counsel throughout the proceeding? Would Zoom’s private chat function be sufficient? Would a defendant be permitted to text with his lawyer? Or will the defendant have to interrupt the proceeding each time he needs to communicate with his counsel? Regardless, requiring the client’s access to his or her attorney to come through video eliminates many of the assurances that come from being in close proximity with one’s lawyer. Likewise, the ability to confer and react in real-time would be greatly reduced.

iv. Remote Video Proceedings Blur the Line Between Waiver and Acceptable Conduct

Still other Sixth Amendment issues may arise when trying to determine issues of waiver of the defendant’s right to be present. The right to be present, like confrontation clause rights, may be waived by a defendant’s voluntary absence and/or due to misconduct by the defendant.{106} 106 See Melendez-Diaz v. Mass., 557 U.S. 305, 314 n.3 (2009), (“The right to confrontation may, of course, be waived.”). For instance, in Illinois v. Allen, the Court upheld the forcible removal of a disruptive defendant from the courtroom.{107} 107 Allen, 397 U.S. at 343. The defendant was repeatedly warned that his conduct would result in removal from the courtroom and that, if he behaved, he would be permitted to return.{108} 108 See id. at 339-40. He did so and was returned to the courtroom.{109} 109 See id. at 341. According to the Court, “[W]e explicitly hold today that a defendant can lose his right to be present at trial if, after he has been warned by the judge that he will be removed if he continues his disruptive behavior, he nevertheless insists on conducting himself in a manner so disorderly, disruptive, and disrespectful of the court that his trial cannot be carried on with him in the courtroom.”{110} 110 Id. at 343 (internal citations omitted).

But webinar platforms, such as Zoom, provide the participant with tools to control when they can be heard or seen. The participants can mute their lines so that no sound can be heard and can also control when their computer’s camera is turned on or off. Could a defendant failing to keep his camera or microphone on constitute a voluntary absence or misconduct befitting a waiver determination? Remote video trials require courts to rewrite the rules of acceptable courtroom behavior.

Likewise, videoconferencing platforms provide the meeting host with tools to control who can be seen and heard. Would a judge’s use of these tools in response to disruptive behavior be appropriate? One might assume so since the Court found binding and gaging a disruptive defendant to be appropriate in certain circumstances,{111} 111 See id. at 344 (“Trying a defendant for a crime while he sits bound and gagged before the judge and jury would to an extent comply with that part of the Sixth Amendment’s purposes that accords the defendant an opportunity to confront the witnesses at the trial. But even to contemplate such a technique, much less see it, arouses a feeling that no person should be tried while shackled and gagged except as a last resort.”). but defense attorneys should be prepared to face these questions and many others as the courts work out a remote video format.

C. Virtual Testimony Would Fundamentally Alter the Psychology of Jurors

i. Moral Suasion on Jurors and Jurists

The ability to observe the defendant during in-person proceedings helps humanize the defendant to the jury. The importance of how proximity affects empathy is embodied in social psychologist Stanley Milgram’s landmark study on power. In the study, Milgram gave his participants the roles of “teachers” and asked them to administer electric shocks to what they were told were other participants (the “learners”). The studies revealed that the closer the teacher was to the learner, the less likely the teacher was to continue administering shocks.{112} 112 S. Milgram, Behavioral Study of Obedience, 67(4) J. Abnormal and Social Psychol. 371-378 (1963). Accordingly, virtual proceedings distance the jurors from the defendant in a way that may affect their empathy for him or her.

The dignification of the defendant is also compromised in virtual proceedings, as it renders the jury unable to see the relationship between a trial attorney and his or her client. Just like the spatial distance between an attorney and a witness that is being cross-examined or the distance between the attorney and the jury box conveys meaning, the distance between a lawyer and his or her client conveys meaning as well.{113} 113 See J.S. Wolfe, The Effect of Location in the Courtroom on Jury Perception of Lawyer Performance, 21(3) Pepp. L. Rev. 731 (1994). Virtual proceedings eliminate the ability of jurors to see the close-knit bond that attorneys develop with their clients, which is manifested in ways such as the attorney lightly touching the client when introducing him or her to the jury panel, how closely they may sit during a trial, or how they interact with one another, whether it be through notes or whispering. This bond can convey respect and signal to jurors that the defendant, irrespective of the allegations, is worthy of that respect.

Overall, the relationship between the defendant and counsel may also suffer through the use of videoconferencing technology, especially if defendant and counsel do not participate in the videoconference from the same room (which would likely be the case due to social distancing guidelines). The defendant may have a difficult time following the proceedings without a lawyer sitting next to him or her explaining what is happening and may be hesitant to voice concerns.

While a defendant’s right to a live proceeding is crucial, it is important to note that the precautions courts are taking in response to the pandemic (e.g., distancing jurors, installing plexiglass in the courtrooms, distributing masks to each juror) will undoubtedly also apply to the defendant. If a defendant has to wear a mask that covers his or her nose and mouth, or the jurors’ view of the defendant is obstructed by plexiglass barriers, jurors will not be able to fully experience the visual and nonverbal cues that are integral to their communication and judgment abilities.

ii. Ability of Jurors to Assess Credibility

When the liberty, and potentially the life, of the defendant are on the line, it is of the utmost importance that the trial court instill in the jury an understanding of the human consequences of their verdict. There is no substitute for the human interaction which takes place in the courtroom.

As anyone who has participated in a videoconference meeting or call with family or friends can attest, it is a poor proxy for face-to-face communication. Multiple articles have been written since COVID-19 forced business and social interactions online about “Zoom fatigue,” the mental exhaustion associated with online videoconferencing.{114} 114 See, e.g., L. Fosslien & M.W. Duffy, How to Combat Zoom Fatigue, Harv. Bus. Rev. (Apr. 29, 2020), https://hbr.org/2020/04/how-to-combat-zoom-fatigue; M. Jiang, The Reason Zoom Calls Drain Your Energy, BBC.com (Apr. 22, 2020), https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20200421-why-zoom-video-chats-are-so-exhausting. Researchers state that remote video calls can drain participants’ energy, in part, because they force us to “focus more intently on conversations in order to absorb information,” as opposed to the nonverbal cues we usually rely upon.{115} 115 Fosslien, supra.

Nonverbal communication is a broad term that encompasses elements such as eye contact, facial expressions, gestures, kinesics (body movement), proxemics (studies of distance), and paralanguage (variations in pitch, speech rate, and volume).{116} 116 See E.A. LeVan, Nonverbal Communication in the Courtroom: Attorney Beware, 8 Law & Psychol. Rev. 83-104 (1984). By one account, 55 percent of communication comes from body language, 38 percent is in the tone of voice, and 7 percent is in the actual words that are spoken.{117} 117 See P. Raj, Body Language and Its Understanding, Submitted to the Faculty of MBICEM (2019), https://www.academia.edu/40938632/Body_Language_and_its_understanding. Putting a trial in a virtual setting compromises nonverbal communication, which has been shown to play an important role in how one’s spoken statements are received. A typical video call, which only frames the participant from the shoulders up, impairs the ability to read many nonverbal cues, such as gestures, and requires sustained and intense attention to words instead. Videoconferencing technology also eliminates the ability to make eye contact, which is often used to assess the confidence of the speaker.{118} 118 See H. Vandromme et al., Indirectly Measured Self-Esteem Predicts Gaze Avoidance, 10 Self and Identity, 1, 32-43 (2011). Virtual proceedings also present a challenge in assessing other nonverbal cues such as pauses in speech and physical mannerisms.

Moreover, video and audio connectivity issues may also reduce the ability to glean anything from micro-expressions or speech patterns. Social psychologist Robert E. Kraut conducted a study in which he had participants judge the truthfulness of a story an actor was telling.{119} 119 See R.E. Kraut, Verbal and Nonverbal Cues in the Perception of Lying, 36 J. Personality and Soc. Psychol. 380-391 (1978). He found that a prolonged pause was viewed as deceptive. Virtual trials could potentially hurt the credibility of a witness if there is a lag in connectivity from the time an attorney finishes asking a question to the time the witness responds. Certain mannerisms, such as rigid posture and relaxed facial expressions, are considered indicative of lying and deceit.{120} 120 See A. Mehrabian, Nonverbal Betrayal of Feeling, J. Experimental Res. in Personality, 1 (1971). Virtual proceedings may distort how jurors use mannerisms in assessing credibility. For example, a defendant or witness may appear rigid if she is experiencing discomfort due to unfamiliarity with the videoconferencing technology. Conversely, a defendant or witness may convey a more relaxed facial expression if he is tuning in from a room in his home.

This is critical as jurors are often instructed to evaluate witness demeanor in determining witness credibility.{121} 121 See U.S. Supreme Court Committee on Standard Jury Instructions. Florida Standard Jury Instructions. Tallahassee: The Florida Bar, 1977, Section 2.2. See also United States v. Johnson, 192 F. App’x 43, 44 (2d Cir. 2006) (“The main charge included a detailed (and sound) instruction on assessing the credibility of witnesses, including the need to evaluate demeanor and nonverbal language.”).

All of this leads to the widely acknowledged statement from the Eleventh Circuit that “confrontation through a video monitor is not the same as physical face-to-face confrontation.”{122} 122 Yates, 438 F.3d at 1315. Jurors’ ability to directly observe the witnesses’ demeanor, body language, and interactions in order to gauge the truth of their statements will be greatly impacted by videoconferencing technology.{123} 123 Some commentators argue face-to-face encounters with witnesses are not necessary and that “the role of demeanor evidence in American trials is seriously overstated” based on psychological research that shows “most people can do no better than chance in determining when a person is telling the truth from observing her in telling the story.” Marcus, supra at 676. However, many jurors believe nonverbal cues are important in determining credibility, though the relative weight and impact of nonverbal communication will necessarily vary for each juror. LeVan, supra at 94-95.

iii. Decreased Juror Attention Spans

As more and more individuals moved to videoconferencing in response to COVID-19, participants reported a tendency to become distracted.{124} 124 See, e.g., S. Gershman, Stop Zoning Out in Zoom Meetings, Harv. Bus. Rev. (May 4, 2020), https://hbr.org/2020/05/stop-zoning-out-in-zoom-meetings. As we consider moving to remote video trials, lawyers and judges must be concerned that jurors will be distracted or fail to pay attention when not in a courtroom.

Under the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments, a criminal defendant is entitled to a fair and impartial jury.{125} 125 See Morgan v. Illinois, 504 U.S. 719 (1992), Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145 (1968). An impartial juror is someone capable and willing to decide the case based solely on the evidence presented at trial.{126} 126 See Smith v. Phillips, 455 U.S. 209, 217 (1982). Juror conduct that prevents a defendant from receiving a fair and impartial trial can warrant a new trial or other action by the court. But juror misconduct, which can include jurors falling asleep or obtaining information from outside sources, is hardly something new in U.S. trials. According to one study, 69 percent of the state and federal judges surveyed had seen at least one juror sleeping during a trial.{127} 127 See, e.g., Sean Carter, Hey, Juror-Juror!, 38 A.B.A.J. 7, 1 (2005) (quoting a study in which 69 percent of state and federal judges had seen at least one juror sleeping during trial). Unfortunately, there is little one can do to ensure jurors provide the defendant with their full attention. Instead, defense attorneys must continue to be vigilant to ensure their client’s right to a fair and impartial jury is not violated by jurors participating in a remote video trial.

impartial jury.{125} 125 See Morgan v. Illinois, 504 U.S. 719 (1992), Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145 (1968). An impartial juror is someone capable and willing to decide the case based solely on the evidence presented at trial.{126} 126 See Smith v. Phillips, 455 U.S. 209, 217 (1982). Juror conduct that prevents a defendant from receiving a fair and impartial trial can warrant a new trial or other action by the court. But juror misconduct, which can include jurors falling asleep or obtaining information from outside sources, is hardly something new in U.S. trials. According to one study, 69 percent of the state and federal judges surveyed had seen at least one juror sleeping during a trial.{127} 127 See, e.g., Sean Carter, Hey, Juror-Juror!, 38 A.B.A.J. 7, 1 (2005) (quoting a study in which 69 percent of state and federal judges had seen at least one juror sleeping during trial). Unfortunately, there is little one can do to ensure jurors provide the defendant with their full attention. Instead, defense attorneys must continue to be vigilant to ensure their client’s right to a fair and impartial jury is not violated by jurors participating in a remote video trial.

For these reasons, and those set forth above, virtual trials are insufficient to protect the rights of criminal defendants.

III. Courts Must Take Steps to Safeguard In-Person Proceedings Against COVID-19

That is not to say that in-person trials may proceed as they did in a pre-pandemic world. To the contrary, the coronavirus imposes unique challenges on jury proceedings. Courts must consider these consequences and develop careful (and transparent) plans to address them prior to resuming operation. In particular, COVID-19 will make it difficult to guarantee a fair cross-section of the community, fair deliberations, a speedy trial, and public access to the proceedings. Each is addressed below.

A. The Pandemic Will Make It Difficult to Obtain a Representative Cross-Section

The Sixth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution guarantees each criminal defendant the right to a trial “by an impartial jury.”{128} 128 U.S. Const. amend. VI. The Supreme Court has held that an “impartial jury” is one drawn from “a representative cross-section of the community.”{129} 129 Holland v. Illinois, 493 U.S. 474, 480 (1990) (“The Sixth Amendment requirement of a fair cross-section on the venire is a means of assuring, not a representative jury (which the Constitution does not demand), but an impartial one (which it does).”). Impartiality requires not only that the jurors chosen are unbiased, but also that the petit jury be selected “from a representative cross-section of the community.”{130} 130 Id. To establish a prima facie violation of the fair cross-section requirement, the defendant must show that (1) a “distinctive” group in the community, (2) is unfairly and unreasonably underrepresented in the venire from which juries are selected when compared to the number of such persons in the community, and (3) that this underrepresentation is due to systematic exclusion of the group in the jury selection process.{131} 131 See Duren v. Missouri, 439 U.S. 357, 364 (1979). If a prima facie violation is established, the jury selection process may only be sustained under the Sixth Amendment if the exclusion “manifestly and primarily” advances a “significant state interest.”{132} 132 Id. at 367-68.

In the wake of the pandemic, courts noted difficulty obtaining a representative cross-section of jurors. This is a key reason courts suspended jury trials with regard to COVID-19. For instance, in its order precluding the calling of jurors for trials, the District Court for the City and County of Denver, Colorado, noted that “[t]hese and other developments with regard to COVID-19 in the geographic area comprising this district adversely affect the Court’s ability to obtain an adequate complement of jurors from a fair cross-section of the community.”{133} 133 Administrative Order No. 2020-04, District Court, City and County of Denver, Colorado, https://www.courts.state.co.us/userfiles/file/Court_Probation/02nd_Judicial_District/Denver_District_Court/Administrative%20Order%202020-04.pdf.

Now, as jury trials get ready to resume, there is very little insight into how COVID-19 will impact juror demographics. Quantitative studies detailing the impact on juror yields are still forthcoming.{134} 134 The National Center for State Courts conducted a survey, which collected information about the average jury yield before the pandemic and monthly jury yield since March 2020. Specifically, they asked courts to provide detailed information about summoning and qualification, including undeliverable, nonresponse/FTA, excusal, and deferral rates. However, its findings have not yet been published. However, certain conclusions can be drawn based on the virus’s trajectory to date. Specifically, jury pools are likely to significantly underrepresent those populations particularly sensitive to infection, including the elderly, persons with comorbid conditions, minorities, low-income individuals, and the unemployed.

i. COVID-19 Will Yield a Self-Selection Bias

There is a real risk that jurors will resent being asked to serve on a jury during a global pandemic. From May 15 to 27, 2020, DRC conducted an anonymous survey of 420 jury-eligible citizens in the counties that comprise the Southern District of New York (i.e., New York, Bronx, Westchester, Rockland, Putnam, Orange, Dutchess, and Sullivan) and the Eastern District of New York (i.e., Kings, Nassau, Queens, Richmond, and Suffolk). The results should sound alarm bells. Seventy-four percent of all respondents indicated that they would be concerned about their health if called to serve as a juror and that they would be anxious about being in close proximity to other potential jurors. In addition, over 65 percent of respondents indicated that they would be anxious about having to take public transportation to commute to the courthouse. Sixty-six percent of respondents stated that they would feel unease being in the courthouse at all — even if the court followed standard safety guidelines (e.g., provided hand sanitizer, required everyone to wear a face-covering or mask, and enforced social distancing). These pervasive anxieties could breed resentment toward the court systems and have the effect of distorting jurors’ judgment in their decision-making at trial — that is, if they show up at all.

Potential jurors may simply ignore the jury summonses and not be willing to risk their well-being. A real likelihood exists that the jury yield will fall into either of two categories — brave souls with a strong sense of civic duty or those ignorant about the coronavirus. This would have the effect of eliminating all other groups. Jury clerks from the respective federal and local jurisdictions need a plan of action — to ensure that defendants’ Sixth Amendment right to a fair cross-section is upheld.

ii. Certain Demographics Will Likely Be Excluded from the Jury Pool

Just what types of demographic groups are likely to be excluded from the jury yield? Those persons particularly vulnerable to the coronavirus — whether based on medical or economic grounds — are particularly likely to be underrepresented.

According to the CDC, individuals aged 65 and older are at a higher risk of severe illness and death from COVID-19.{135} 135 See COVID-19 Guidance for Older Adults, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/aging/covid19-guidance.html (last accessed May 28, 2020). In jurisdictions where in-person jury trials resume, it is likely the elderly will be underrepresented on jury venires because they are less likely to leave their homes until the pandemic has subsided. The elderly may also be at a disadvantage in attending proceedings virtually, depending on their access to the hardware and ability to navigate the software. While most jurisdictions allow individuals older than 70 to opt-out of jury service, these individuals should be allowed to serve if they want. The current state of affairs will effectively prevent them from doing so.

b. Persons with Comorbid Conditions

Some courts have also taken steps to exclude high-risk individuals from the jury pool. For instance, the Contra Costa County Court stated that individuals who are “immunocompromised” may be excused from service upon providing sufficient proof.{136} 136 See Superior Court of California, County of Contra Costa, Urgent Release: Court Reopening (May 13, 2020), https://www.cc-courts.org/general/docs/PressRelease-COVID19-05-13-20.pdf.

What constitutes a high-risk individual? The China Medical Treatment Expert Group for COVID-19 analyzed data from 1590 laboratory-confirmed hospitalized patients from 575 hospitals across mainland China between December 11, 2019, and January 31, 2020.{137} 137 W. Guan et al., Comorbidity and Its Impact on 1590 Patients with COVID-19 in China: A Nationwide Analysis, 55(5) Eur. Respir. J. (May 2020), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7098485/. It found that 20–51 percent of COVID-19 patients were reported as having at least one comorbidity, with diabetes (10–20 percent), hypertension (10–15 percent) and other cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases (7–40 percent) being most common. Previous studies have demonstrated that the presence of any comorbidity has been associated with a 3.4-fold increased risk of developing acute respiratory distress syndrome in patients with H7N9 infection.{138} 138 See id. (citing H.N. Gao et al., Clinical Findings in 111 Cases of Influenza A (H7N9) Virus Infection, 368 N. Engl. J. Med. 2277–2285 (2013), https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/nejmoa1305584). Of course, COVID-19 is more readily predisposed to respiratory failure and death in susceptible patients.