The holding in Brady v. Maryland1 has been the law since 1963, and yet it is incredibly underutilized by the defense bar throughout the United States. The decisions in Brady, United States v. Bagley,2 and Kyles v. Whitley3 have predominately dictated the requirements of the prosecution to turn over all materials that include the following: (1) information that would exonerate the accused; (2) exculpatory information; (3) information that would lessen the punishment; (4) all material impeachment of the government’s evidence or witnesses; and (5) any evidence that would support a valid defense. But the defense must ask for it.

What Happened in Brady?

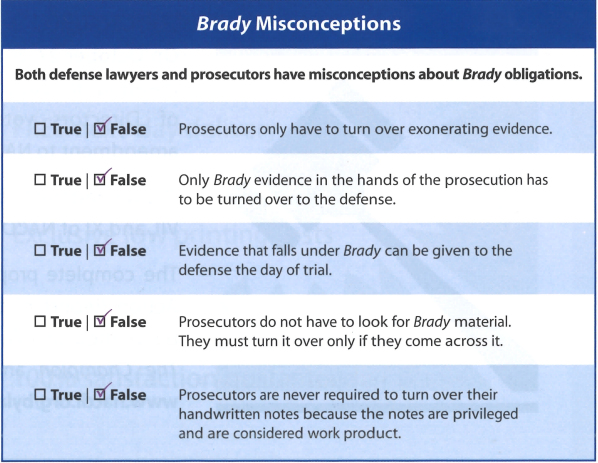

The facts in Brady are worthy of discussion. John Leo Brady was on trial for first-degree murder in the state of Maryland. His lawyer conceded guilt (as the evidence was overwhelming) but sought to save him from capital punishment. He was charged with a co-defendant named Charles Boblit. Brady was found guilty and sentenced to death. After the conclusion of all appeals and postconviction matters, Brady learned that the state had withheld a statement made by his co-defendant which, although it implicated Brady in the crime, excluded him as the actual killer. Brady argued that failing to turn over the statement to his defense team violated due process. His position was that had the jury learned that he did not do the actual killing, the jury would have voted to spare his life. The U.S. Supreme Court did not reverse his conviction but did reverse for a new sentencing hearing. Most lawyers believe that the principles in Brady have to do with the prosecution turning over evidence that would exonerate the accused. In actuality, it was not exonerating in nature but rather it was exculpatory and impeaching in nature.

What Must the Prosecution Turn Over?

Prosecutors are required to turn over far more than exonerating evidence, and the Bradydisclosure obligation is not limited to information of which the prosecutor has actual knowledge. Rather, the prosecutor has a nondelegable duty to learn of Brady information in the case. All evidence that would fall under Brady in the hands of law enforcement and other investigative agencies is chargeable to the prosecution. In other words, if the police know, even when they do not tell the prosecutor, the government is charged with knowing. Kyles v. Whitley made it very clear:

Prosecutors are required to turn over far more than exonerating evidence, and the Bradydisclosure obligation is not limited to information of which the prosecutor has actual knowledge. Rather, the prosecutor has a nondelegable duty to learn of Brady information in the case. All evidence that would fall under Brady in the hands of law enforcement and other investigative agencies is chargeable to the prosecution. In other words, if the police know, even when they do not tell the prosecutor, the government is charged with knowing. Kyles v. Whitley made it very clear:

This … means that the individual prosecutor has a duty to learn of any favorable evidence known to the others acting on the government’s behalf in the case, including the police.4

Furthermore, the prosecution cannot provide vast amounts of evidence that may contain Bradymaterial at a time so close to trial that it cannot be properly reviewed and utilized.5 And it may not hide Brady ma

terial of which it is actually aware in a huge open file in the hope that the defendant will never find it. Doing so would indicate that the government is acting in bad faith in performing its obligations under Brady.6 Nor may prosecutors dump mountains of documents on defense lawyers and leave them unguided as to materiality.7

Although the government does not have to turn over inadmissible evidence to the defense,8 it does have to turn over anything that might lead to admissible evidence. For example, although the results of a polygraph examination may not be required to be turned over, the fact that the pretest interview differs from the post-test interview in material ways would in fact require disclosure because it contains material impeachment that could be used to cross-examine the witness at trial. The only way the prosecutor would not be required to turn over such impeachment would be if the witness was withdrawn from the prosecution witness list or the defense and prosecution are actively engaged in plea negotiations.9 This is permitted when impeachment information is present but never when such information would exonerate the accused. There are no exceptions when that is the case.

Preservation Letter

A tactic that may be employed by the defense attorney soon after arrest is to send a “preservation letter” to the assigned prosecutor and to the lead detective, agent, or law enforcement officer. The letter requests that the government obtain and preserve all evidence that bears upon the prosecution (and defense) of the case. The letter should be sent certified to assure its receipt. Why should the preservation letter also be sent to the lead law enforcement officer when it is the prosecutor who is responsible for the collection of Brady material? It is true that the prosecutor is charged with uncovering all Brady material in the prosecutor’s office as well as Brady material contained in law enforcement files and related agencies working on behalf of the government in the underlying prosecution. The benefit of sending the letter to law enforcement is for use at trial. Rarely will anyone from law enforcement provide anything asked for or even respond to the letter.

Jurors are hungry to learn all the information in a case in order to render the proper verdict. They do not want to be shortchanged. It then becomes a fertile area during cross-examination to ask if, in the lead detective or agent’s opinion, he or she conducted a “fair, complete and exhaustive” investigation of the case:

Defense Counsel: Do you agree that the jury is entitled to hear all relevant evidence collected by the government?

Lead Detective: Yes.

(Now counsel has cornered the detective.)

Defense Counsel: Did you receive the letter I sent you asking that you obtain and preserve all the evidence related to this case?

(The letter can be marked into evidence and shown to the witness.)

Lead Detective: Yes.

Item by item, defense counsel can ask the detective if he or she searched for the information requested and obtained it “so that the jury would have the benefit of this important evidence in deciding the case.” The detective’s response will not be accepted by the jury. “It’s not my job to collect evidence for you” is not an answer the jury will accept. “The prosecutor never asked me to gather this information” is not a response jurors will find satisfactory.

‘Ethical Rule’ Order

In an article published in 2013, NACDL Past President Barry Scheck and former U.S. District Judge Nancy Gertner recommended that defense lawyers file a motion for an “ethical rule” order for the disclosure of favorable evidence.10 The basis of the motion is Rule 3.8(d) of the ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct. Rule 3.8(d), which has been adopted by 49 states, addresses the responsibilities of the prosecutor:

The prosecutor in a criminal case shall … make timely disclosure to the defense of all evidence or information known to the prosecutor that tends to negate the guilt of the accused or mitigates the offense, and, in connection with sentencing, disclose to the defense and to the tribunal all unprivileged mitigating information known to the prosecutor, except when the prosecutor is relieved of this responsibility by a protective order of the tribunal.11

The rule also provides for an in camera production when privileged or sensitive information may be involved.12

The ethical rule order would require the prosecution to search prosecution and investigative files and then verify that disclosure has been made of all information that falls within the order. The Rule 3.8 motion should be made in conjunction with any state rule that bears upon Bradydisclosure. The order submitted to the court, if granted, provides for the production of such information to the defense within a certain number of days of the order. Further, it allows for the production of such additional information that falls within the government’s continuing obligation to disclose. A violation of the court’s granted order may result in contempt proceedings against the prosecutor. Along with a request made under Rule 3.8, defense counsel should file a more specific motion for the disclosure of Brady material.

Search, Find, Disclose

So, what must the defense lawyer do to require the prosecution to fulfill its obligations under Brady? “Do nothing” is the wrong answer. The defense lawyer cannot sit back and expect the prosecutor to fulfill his or her obligations. A specific Brady motion must be filed and calendared for hearing. Specific areas must be listed for the prosecutor to search and report back on each area. If defense counsel does not file a motion, it is the prosecutor who decides what to look into and what to turn over to the defense. The reasoning behind the filing of a specific motion can be found in United States v. Bagley:

And the more specifically the defense requests certain evidence, thus putting the prosecutor on notice of its value, the more reasonable it is for the defense to assume from the nondisclosure that the evidence does not exist, and to make pretrial and trial decisions on the basis of this assumption. … [T]he reviewing court may consider directly any adverse effect that the prosecutor’s failure to respond might have had on the preparation or presentation of the defendant’s case.13

The defense team should request that the prosecutor search for, obtain, and disclose the following items:

The defense team should request that the prosecutor search for, obtain, and disclose the following items:

- Emails (prosecutor to police, police to prosecutor, state witnesses to police or prosecutor and police or prosecutor to witness, lay and expert).

- Text messages and instant messages.

- Messages between officers or officer to station.

- Two-way dispatch messages.

- 911 calls.

- Audiotapes and videotapes (including those captured via body cameras or cellphone cameras).

- Records stored, sent, or received via Dropbox or similar cloud computing or FTP (file transfer protocol) websites.

- All electronic devices including but not limited to computers, laptops, iPads, cellular phones and smartphones that may contain discoverable material.

- All social media accounts that may bear upon the prosecution including but not limited to Facebook, Google, AOL, Yahoo, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat, and any online cloud backups that may contain information related to the prosecution.

- All handwritten notes of law enforcement officers to be reviewed in camera for Brady material.

- All handwritten or memorialized notes of the prosecutor concerning witness interviews of law enforcement officers, experts, and lay witnesses involved in the prosecution (in camera). Such notes are intended to include, but are not limited to, investigations and trial preparation of witnesses.

- All medical records including psychiatric and clinical reports that may have relevance to the prosecution or to any valid defense, including those covered by HIPPA (in camera).

- All electronic devices, including cellphones and computers, belonging to witnesses listed by the government that may contain Brady material.

- The name and address of any witness known to the prosecution who has given a statement to the prosecution or law enforcement that is contrary to the prosecution’s theory of the case, including pre-interviews and post-interviews conducted during polygraph testing.

- Any favorable treatment of any kind given or offered to any government witness in return for cooperation as well as any favorable treatment, money, or anything of value requested by a state witness in return for cooperation.

- Any social media postings made by the alleged victim relevant to the case, including those that were taken down but can be retrieved by the government.

- All contents of investigative and professional files relative to the prosecution, including notes, memorandum, and reports. This also applies to the notes of any witness coordinator.

Defense lawyers should be concerned that prosecutors may come across impeachment or exculpatory evidence and not believe, in their opinion, that it is “material.” If they do, they will decide not to turn it over to the defense. The problem arises when the defense would have determined that the information was in fact material and could be effectively used at trial. To combat this problem, the defense should consider filing a motion for an in camera review of all evidence that the government has determined not to be material and therefore not turned over to the defense. This “nonmaterial log” should detail things prosecutors have not turned over to the defense and their reasons for not doing so. The court then makes the final decision in camera. (Most often the judge will not risk error and will turn it over to the defense.)

The DOJ Memo

In 2010, the Department of Justice provided guidance to all assistant United States attorneys handling criminal cases about their obligations under Brady v. Maryland.14 That memorandum, titled “Memorandum for Department Prosecutors,” began by noting the prosecution’s obligation and specifying who is on the prosecution’s team:

It is the obligation of federal prosecutors, in preparing for trial, to seek all exculpatory and impeachment information from all members of the prosecution team. Members of the prosecution team include federal, state, and local law enforcement officers and other government officials participating in the investigation and prosecution of the criminal case against the defendant.

It is the obligation of federal prosecutors, in preparing for trial, to seek all exculpatory and impeachment information from all members of the prosecution team. Members of the prosecution team include federal, state, and local law enforcement officers and other government officials participating in the investigation and prosecution of the criminal case against the defendant.

In the “what to review” section, the guidance directs the prosecutor to look into the following (as well as other) non-exhaustive areas:

- The investigative agency’s entire investigative file, including documents such as electronic communications, inserts, and emails, should be reviewed for discoverable information. Should sensitive information ordinarily not discoverable be contained within the review document, the entire document is not necessarily discoverable but rather only the discoverable information contained in it.

- Confidential informant information should be reviewed in its entirety, including past cases in which the confidential informant cooperated. It should include all proffers, immunity, and other agreements. Validation assessments, payment information, and other potential witness impeachment information should be included within this review.

- Substantive case-related communications may contain discoverable information. They are most likely to occur (a) among prosecutors and/or agents, (b) between prosecutors and/or agents and witnesses and/or victims, and (c) between victim-witness coordinators and witnesses and/or victims. Such communications may be memorialized in emails, memoranda, or notes. “Substantive” communications include factual reports about investigative activity, factual discussions of the relative merits of evidence, factual information obtained during interviews or interactions with witness/victims, and factual issues relating to credibility. (Note: material exculpatory information that the prosecutor receives during a conversation with a law enforcement officer or witness is no less discoverable than if that same information were contained in an email.)

- The prosecutor should not only look into any benefit that a witness may have in testifying against the defendant, but also should look into known conditions that could affect the witness’s bias such as animosity toward the defendant, animosity toward a group of which the defendant is a member or with which the defendant is affiliated, relationship with victim, known but uncharged criminal conduct that may provide an incentive to curry favor with a prosecutor, and known substance abuse or mental health issues or other issues that could affect the witness’s ability to perceive and recall events.

- Information obtained in witness interviews whether memorialized in writing or overheard by law enforcement officers or prosecutors. Any material variance in a witness’s statements should be memorialized and turned over to the defense as Giglio information.

- Trial preparation meetings with witnesses are also subject to a Brady review. New information that is exculpatory or impeachment information should be disclosed to the defense.

- Police officers’ notes should be reviewed to determine whether they contain material impeachment or exculpatory information. Particular attention should be paid to notes gathered during discussions with the defendant or material witnesses.

The memorandum to federal prosecutors points out that their duty is to “seek” all exculpatory and impeachment information from all members of the prosecution team. The word “seek” is important because it puts the onus on prosecutors to go out and find Brady material as opposed to Brady material finding them. The Court in Kyles v. Whitley noted: “A prosecutor has a duty to learn of any favorable evidence known to the others acting on the government’s behalf in the case. …”

That duty to learn means that the government cannot just sit back and turn over whatever Bradymaterial is given to it. Instead, prosecutors must go out and affirmatively search for it. And perhaps the reasoning behind that stringent requirement can be found in United States v. Bagley:

By requiring the prosecutor to assist the defense in making its case, the Brady rule represents a limited departure from a pure adversarial model. The Court has recognized, however, that the prosecutor’s role transcends that of an adversary: he “is the representative not of an ordinary party to a controversy, but of a sovereignty … whose interest … in a criminal prosecution is not that it shall win a case, but that justice shall be done.”15

Conclusion

That’s right, by requiring the prosecutor “to assist the defense in making its case” is the language in Bagley. What a statement! The U.S. Supreme Court is telling prosecutors and others on the government’s team that they have an obligation to help the defense to acquire all information that is deemed “Brady material.” In other words, “hide the ball” is not only unacceptable but also is condemned. But defense lawyers cannot be naive. Expecting the government to play by the rules and go out and look for evidence that will free their clients is nothing defense lawyers should count on or anticipate. Motions must be filed, hearings set, and follow up conducted so that every stone is unturned and accounted for. John Leo Brady is a perfect example of why the rule is not self-executing. Defense lawyers must wake up this sleeping giant and hold the prosecution to its obligation to go out and look for and turn over all Brady material. If and when they do, reasonable doubts will begin to appear.

Notes

- 373 U.S. 83 (1963).

- 473 U.S. 667 (1985).

- 514 U.S. 419 (1995).

- Id. at 437.

- See Miller v. United States, 14 A.3d 1095 (D.C. 2011) and Perez v. United States, 968 A.2d 39 (D.C. 2009).

- See United States v. Skilling, 554 F.3d 529 (5th Cir. 2009).

- See United States v. Bortnovsky, 820 F.2d 572 (2d Cir. 1987).

- Wood v. Bartholomew, 516 U.S. 1 (1995) (results of a polygraph given to a government witness). Polygraphs are not admissible in federal court. In states that do admit polygraph evidence, however, the polygraph of a government witness is subject to being produced by the government pursuant to Brady.

- United States v. Ruiz, 122 S. Ct. 2450 (2002).

- Barry Scheck & Nancy Gertner, Combatting Brady Violations with an ‘Ethical Rule’ Order for the Disclosure of Favorable Evidence, The Champion, May 2013, at 40.

- Model Rules of Prof’l Conduct 3.8 (1983).

- See Model Rules of Prof’l Conduct 3.8 cmt. 3 (1983).

- 473 U.S. 667, 682-3.

- Read the memorandum at https://www.justice.gov/archives/dag/memorandum-department-prosecutors.

- 473 U.S. 667 n.6 (quoting Berger v. United States, 295 U.S. 78, 88 (1935).

About the Author

Denis deVlaming has lectured around the United States on matters pertaining to Brady and published numerous articles touching on criminal law. He is board certified in criminal trial law and teaches Advanced Criminal Trial Advocacy as an adjunct professor at Stetson College of Law.

Denis deVlaming (NACDL Life Member)

deVlaming & Rivellini, P.A.

Clearwater, Florida

727-461-0525

denis@deVlaming.com

www.devlaming.com