At the onset of COVID in March of 2020, most jurisdictions placed jury trials on a temporary hold, unsure how long the pandemic would last. Today, following over a year of trial delays and suspensions, courts are scrambling to make up for lost time. With both public safety and core constitutional rights on the line, courts across the country have experimented with the implementation of virtual trials and other remote proceedings. For defense lawyers and their clients, this growing practice is cause for concern as it carries unique threats for the constitutional rights of those accused. At the same time, virtual trials have also brought about benefits for the administration of justice, raising the possibility for certain practices to be carried into a post-COVID world. In the months and years to come, courts will be forced to weigh the benefits of virtual jury trials without losing sight of the core rights of accused individuals.

Jump to:

Virtual Trial Concerns Virtual Trials Benefits Additional Resources

Virtual Jury Trials

Weeks into lockdown, with no sign that courts would be able to resume at full capacity any time soon, jurisdictions began experimenting with remote proceedings, ranging from pretrial hearings to civil and criminal jury trials.

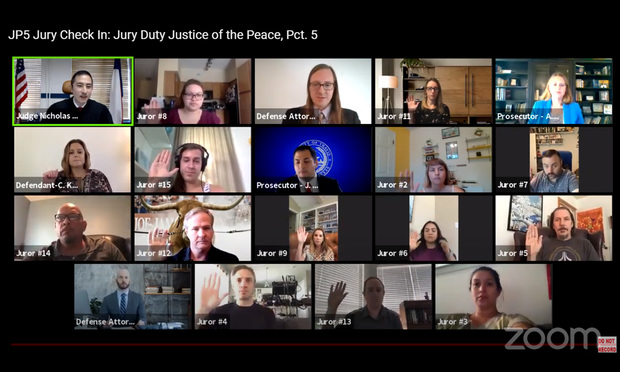

On May 18th, 2020, in northeast Texas, Collin County Courthouse held what was likely the nation’s first remote civil jury trial. 26 potential jurors convened on Zoom from their homes for a case originally scheduled to go to trial in March 2020.

“You’re not at home on jury duty. You’re on jury duty. You just happen to be at home. The courthouse came to you.” – Retired Judge Keith Dean, Collin County Courthouse, Texas

Further south, Travis County, Texas began implementing virtual jury trials as well. On August 11th, 2020, in the nation’s first remote criminal jury trial, jurors weighed the evidence in a misdemeanor case involving a woman accused of speeding while in a construction zone.

Virtual Jury Trial Concerns

Although virtual jury trials proved to be much safer for those involved than gathering in person during the pandemic, they have raised several constitutional and logistical concerns, calling into question their transferability into a post-COVID world.

At the height of the pandemic, virtual trials appeared to be a viable alternative to an in-person trial without causing unreasonable delay. However, the Sixth Amendment does not only outline the right to a speedy trial by jury. An accused must also receive representation from counsel and an opportunity to confront witnesses, and their trial must be public with an impartial and representative jury. By prioritizing individuals’ right to a speedy trial and implementing virtual jury proceedings, courts have jeopardized other equally fundamental Sixth Amendment rights.

“In assessing the viability of alternative processes including virtual or remote hearings, courts must avoid placing an accused in a position in which s/he must elect between one set of rights to the detriment of others” – NACDL Report, Criminal Court Reopening and Public Health in the COVID-19 Era

Right to Counsel

Of all the Sixth Amendment rights, guaranteeing to access to counsel appears to be at least partially transferable into the virtual atmosphere. However, the switch to virtual communication still raises concerns for confidential attorney-client communication.

During the pandemic, with most correctional facilities on lockdown, many attorneys were not permitted to visit their clients in person, inhibiting their ability to prepare for a virtual trial, build a relationship, and gather necessary information around their client’s case. Some facilities made video conferencing or telephone calls available, however confidential opportunities could be subject to strict time constraints. This type of virtual communication also limits nonverbal cues such as facial expressions or a handshake, both of which play a key role in establishing trust.

Ensuring access to confidential attorney-client communication continues to present challenges at virtual trials. Courts have worked to mitigate this using Zoom breakout rooms or by encouraging clients and attorneys to communicate via phone call or text, though the latter hinges on access to a phone. Despite these temporary solutions, the ease of attorney-client communication is nevertheless greatly inhibited by virtual proceedings, almost eliminating the ability for counsel to casually converse with their client throughout the trial.

Confronting Witnesses in Court

The Sixth Amendment also guarantees that "in all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right…to be confronted with the witnesses against him." This right was established to prevent an individual from being convicted solely from written evidence, such as affidavits, without having the opportunity to evaluate the veracity of witness and victim statements before a jury.

Learn more about the confrontation clause

The Supreme Court has established a precedent of strictly interpreting the Confrontation Clause. In Coy v. Iowa (1980), the Court held that Mr. Coy’s Sixth Amendment rights had been violated during trial when the court placed a physical screen in between him and the two victims during their testimony. They found that this infringed upon Coy’s right to confrontation, which is " essential to fairness," as it provides an opportunity for a full examination of the facts and statements in the case. In 1990, however, Supreme Court’s ruling in Maryland v. Craig concluded that there are circumstances in which the Confrontation Clause could be overridden if sufficient alternatives are provided. Craig established a two-prong test for evaluating exceptions to the Confrontation Clause: “where denial of such confrontation is necessary to further an important public policy and the reliability of the testimony is otherwise assured.” Despite this decision, virtual testimony remains a rare, “case-specific” exception to the right to in-person confrontation. As the Court stated in Craig, the ability to engage in face-to-face confrontation remains one of “the core of the values furthered by the Confrontation Clause” as “it enhances the accuracy of [fact-finding] by reducing the risk that a witness will wrongfully implicate an innocent person.”

Over a decade later, the Supreme Court ruled on Crawford v. Washington (2004), dismissing the idea that “reliable” out-of-court testimony was constitutional. Instead, an accused individual should have the opportunity to confront and cross-examine all “testimonial” evidence presented in court, unless a witness is unavailable, or the accused individual and their attorney had already been given an opportunity for cross-examination.

With this precedent, when the pandemic hit, it was not altogether clear if virtual testimony would fulfill the requirements of the Confrontation Clause. In March of 2020, the Confrontation Clause faced one of its first tests when the Michigan Supreme Court ruled on People v. Jemison, prohibiting a DNA analyst from testifying over Skype, stating that video testimony did not provide sufficient opportunity for in-person cross-examination. In the United States v. Casher (2020), a Montana federal district court also barred remote testimony from two out-of-state witnesses, noting that the alleged “risks do not represent a ‘necessity’ to forego physical confrontation” as “traveling by car and taking precautions recommended by the CDC” were reasonable alternatives. In contrast, the Southern District of New York federal court ruled in United States v. Donziger (2021) that a medically vulnerable witness would be permitted to testify virtually from a courtroom in Dallas, Texas. The judge justified this decision on the grounds that “limiting the spread of COVID-19 and protecting at-risk individuals from exposure to the virus are critically important public policies.”

As the direct risks of contracting COVID in a courtroom decrease, unanswered questions around the role of virtual testimony remain. Will remote witnesses in criminal trials continue to be allowed on a case-by-case basis? Will virtual testimony become the norm once virtual trials are no longer required to protect public health? These questions and more will continue to play out as courts across the country navigate holding jury trials over the next couple of months and years.

Public Trial

Accused individuals are additionally guaranteed the right to a public trial under the Sixth Amendment. Public access, including the general public, members of the press, and those connected with the accused individual and victim, serves as both a measure of accountability and a method of fostering trust for the judicial process. However, like the Confrontation Clause, this right is also accompanied by exceptions.

In Waller v. Georgia (1984) the Supreme Court set forth a four-prong test to evaluate whether a court closure complies with the Sixth Amendment. To justify a court closure to the public, “the party seeking to close the hearing must advance an overriding interest that is likely to be prejudiced; the closure must be no broader than necessary to protect that interest; the trial court must consider reasonable alternatives to closing the hearing; and it must make findings adequate to support the closure.” This language invokes a level of strict scrutiny, requiring the government to establish an “overriding interest” that the closure is necessary and narrowly tailored to further such interest. In the past, courts have permitted “overriding interests” that relate to the safety and privacy of certain witnesses, victims, or accused individuals. For example, in Rodriguez v. Miller (2008) the court permitted a closed trial to protect the identity of an undercover officer.

In the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, the government has argued that it has a clear overriding interest, and perhaps even an obligation, to protect public health and safety (Mead v. Holder, 2011; Legatus v. Sebelius, 2012). With respect to the second prong of the test, the government must also be able to demonstrate that the closure is “no broader than necessary” and that all reasonable alternatives have been exhausted. This proves to be relatively simple: if individuals were to comply with social distancing regulations, as well as whatever limits on gatherings were in place at the time, there would not be enough space in the courthouse to appropriately accommodate the public.

The case law explored up to this point has largely focused on the right to a public trial during in-person proceedings. However, as courts began holding remote trials, public access in the virtual space took on a new meaning. Many courts have launched livestreams of their proceedings on YouTube, and the Texas judicial branch went as far as to set up a YouTube channel, including links to their current livestreams and a schedule of past recordings. While this increased access carries benefits for public engagement and transparency, livestreams have presented privacy concerns for those involved in the proceedings. First, there is no way to ensure that viewers do not record court proceedings, raising the possibility that someone could record and distribute sensitive case information after the fact. Additionally, particularly in sensitive cases relating to children or domestic abuse, livestreams greatly expand the reach of the personal information of those involved. Advocates have further raised safety concerns for victims and witnesses, fearing they may receive retribution for testifying.

With the measurable benefits to public access, the practice of live streaming trials may be here to stay. In the recent high-profile case against Derek Chauvin, the public had live, virtual access to the in-person proceedings, allowing individuals from all over the world to closely follow the case and verdict. This new trend will continue to play out as courts increasingly return to in-person trials, forcing courts to balance the interests of access and transparency with the privacy concerns and safety of those involved in the case.

Impartial and Representative Juries

In Sheppard v. Maxwell (1966), the Supreme Court held that for a jury to be impartial, it must not be exposed to extrajudicial information. While in a typical jury trial, jurors may be required to temporarily turn in their phones, restricting access to technology is nearly impossible outside the confines of a courtroom. Virtual trials additionally pose potential challenges and benefits to securing a representative jury. On one hand, by allowing jurors to participate from their homes, the process becomes more easily accessible, eliminating the need for transportation to and from the court. At the same time, however, virtual trials do require access to reliable broadband, and a Zoom-compatible device, both of which are impacted by an individual’s financial means.

Learn more about representative juries during COVID-19

Technological Concerns

In addition to specific constitutional concerns, conducting virtual jury trials presents unique logistical issues and risks dehumanizing the trial experience.

As with all remote meetings, there is no clear way to ensure that individuals are devoting their undivided attention to the proceedings at hand. Additionally, to even participate in virtual court, individuals must have a working device with internet and feel comfortable operating that device. To mitigate this barrier, some courts in Texas have distributed an online questionnaire before the trial to inquire about prospective jurors’ access to technology and a private space to participate. Any jurors who indicated that they needed technology were loaned iPads with cell service.

The use of technology in trials also risks trivializing an incredibly critical process for accused individuals, turning court proceedings into just another Zoom meeting. As NACDL’s report Criminal Court Reopening and Public Health in the COVID-19 Era states “separating an accused person from the jury by virtual mechanisms (or plexiglass or mask for that matter) dehumanizes the person on trial and reduces juror empathy,” creating an unfair court dynamic. In criminal jury trials, where an individual’s liberty is at stake, in-person proceedings allow jurors to evaluate the accused individual as a fellow person, instead of simply face on a distanced screen.

Typical credibility assessments also become more complicated in remote settings as individuals lose out on the 55% of communication that is non-verbal, such and body language and eye contact. This represents a significant loss for jurors, attorneys, and judges who are tasked with evaluating the merits of testimony and evidence.

Potential jurors take the oath to participate in the nation's first virtual criminal jury trial on August 11th, 2020.

Virtual Jury Trial Benefits

Despite the constitutional and technological concerns surrounding virtual trials, courts have also discovered many unintended benefits of incorporating technology into the judicial process, primarily related to logistics and time savings.

For jurors, accused individuals, victims, attorneys, judges, and witnesses alike, virtual proceedings drastically cut down on the time required for each case. By eliminating travel to and from the courthouse, individuals can participate in a trial without having to coordinate childcare or interrupt a full day of work. Similarly, virtual court is much more accessible for family and friends of those involved in the trial, particularly for individuals who may be out of state. The practice of livestreaming cases has also drastically expanded access to trials, allowing the general public to virtually engage with the judicial process. In a court case in April of 2020, the Kansas Supreme Court reported that over 3,500 people watched the oral arguments take place, a number that would have been previously unheard of in a physical courtroom.

Further, holding virtual court saves the court dockets time, which is particularly noteworthy given the current state of COVID-related backlogs throughout the country.

Learn more about court backlogs

In rural jurisdictions, the convenience of remote proceedings may prove to be particularly useful when recruiting witnesses to testify. Instead of having to recruit experts locally or pay them to travel long distances to attend court, attorneys can broaden their virtual network to identify the most qualified and specialized expert for their case.

At this point, it is unclear whether virtual trials or other proceedings are here to stay. The benefits of the virtual courtroom are measurable: from time savings to increased accessibility and transparency. Yet, at the same time, significant Sixth Amendment concerns remain around how the rights afforded to individuals accused of crimes will play out in the coming months with courts ramping up in-person proceedings, streaming trials live on the internet, and working to remedy case backlogs.

Additional Reading

The Practical and Constitutional Issues with Virtual Jury Trials in Criminal Cases (ABA, February 26th, 2021)

Constitutional Concerns Related to Jury Trials During the COVID-19 Pandemic (National Center for State Courts, February 22nd, 2021)

Jury Selection in the Age of COVID-19 (ABA, December 17th, 2020)

Virtual Criminal Courts (Deniz Ariturk, William E. Crozier and Brandon L. Garrett, The University of Chicago Law Review, November 16th, 2020)

How Video Changes the Conversation: Social Science Research on Communication Over Video and Implications for the Criminal Courtroom (Center for Court Innovation and National Legal Aid and Defender Association, November 2020)

The Constitution Is On Pause in America’s Courtrooms (The Atlantic, October 10th, 2020)

In Practice | Virtual Court: Barriers to Access and Fairness at Initial Appearances (Center for Court Innovation, September 2020)

Can You Get A Fair Jury Trial During The Pandemic? (Cara Bayles, Law 360, August 30th, 2020)

And Justice for None: How COVID-19 Is Crippling the Criminal Jury Right (Brandon Marc Draper, Boston College Law Review, August 28th, 2020)

Jury Trials During the COVID-19 Pandemic (Office of Court Administration for the State of Texas, August 28th, 2020)

How Litigators Are Confronting COVID in the Courtroom (ABA, August 2020)

Jury Trials in a (Post) Pandemic World – National Survey Analysis (National Center for State Courts, June 22nd, 2020)

Criminal Court Reopening and Public Health in the COVID-19 Era: NACDL Statement of Principles and Report (NACDL, June 2020)

The Right to a Public Trial in the Time of COVID-19 (Stephen Smith, Santa Clara Law Review, May 2020)

COVID-19’s Next Victim? The Rights of the Accused (NACDL, May 2020)

Next Pre-Trial Question for Jurors: Are You Vaccinated? (Bloomberg Law, May 2021)

Webinars

COVID-19 and Criminal Trials: Lessons for the Future (October 16, 2020)

Professor Andrea Roth discusses how COVID-19 has affected criminal trials: the challenges, opportunities, and lessons for the future.

Reestablishing Jury Pools in the COVID-19 Era (June 4, 2020)

The first step in resuming jury trials involves summoning and qualifying a pool of prospective jurors from which to select juries. In addition to suspending jury trials since mid-March, most courts stopped mailing jury summonses. This webinar provides information to help jury operations ramp back up, including recommendations for excusal, deferral, and FTA policies. It also addresses concerns about jury pools that may underrepresent racial and ethnic minorities due to their increased risk of severe health consequences from the COVID-19.