Page Hero

Impartial & Representative Juries

The Sixth Amendment states that "[i]n all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to . . . trial, by an impartial jury...." The focus on jury impartiality was rooted in the desire to preserve individual liberty in the face of a tyrannical government.

Resources on Impartial and Representative Juries

IN SEARCH OF IMPARTIALITY

The Sixth Amendment right to an impartial jury is rooted in “the essential demands of fairness.” Aldridge v. United States, 283 U.S. 308, 310 (1931). Prosecutors and defense attorneys alike use the pre-trial process of voir dire to determine if a potential juror can be fair and impartial during trial. During voir dire, the prosecutor, defense attorney and the judge question jurors in order to identify any potential biases, prejudices, or conflicts of interest that may improperly impact case outcomes. If either party identifies potential biases, that juror may be eliminated "for cause" meaning the challenging party can articulate a legitimate basis for eliminating that juror. Peremptory challenges are the vehicle litigants use to express an arbitrary challenge to a potential juror "without cause."

Peremptory challenges are a “creature of statute,” Ross v. Oklahoma, 487 U.S. 81, 89 (1988), that aren't derived from Sixth Amendment rights or in the right to an “impartial jury.” See, e.g., United States v. Martinez-Salazar, 528 U.S. 304, 311 (2000). Therefore an improper denial of the use of a peremptory challenge is not a Sixth Amendment or Federal constitutional violation.

REPRESENTATIVE JURIES

One of the primary issues impacting jury impartiality in jurisdictions across the country is the under-representation of racial and ethnic minorities. This dynamic has historic origins as women and minorities were systematically excluded from jury service. The Supreme Court has since attempted to address these issues by generating a rule that requires juries be selected from a "fair cross-section" of society.

The selection of a petit jury from a representative cross section of the community is an essential component of the Sixth Amendment right to a jury trial.

-Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522, 528 (1975)

Jury pools that are a result of “systematic exclusion” in the selection process violate the fair cross section guarantee.

In order to establish a prima facie violation of the fair-cross-section requirement, the defendant must show (1) that the group alleged to be excluded is a ‘distinctive’ group in the community; (2) that the representation of this group in venires from which juries are selected is not fair and reasonable in relation to the number of such persons in the community; and (3) that this underrepresentation is due to systematic exclusion of the group in the jury-selection process." Duren v. Missouri, 439 U.S. 357, 364 (1979).

The Court has not defined the term "distinctive," but indicated that it " must be linked to the purposes of the fair cross-section requirement." Lockhart v. McCree, 476 U.S. 162 (1986), In Taylor v. Louisiana, the Court described the purpose of the fair cross-section requirement as (1) "guard[ing] against the exercise of arbitrary power" and ensuring that the "common sense judgment of the community" will act as "a hedge against the overzealous or mistaken prosecutor," (2) preserving "public confidence in the fairness of the criminal justice system," and (3) implementing our belief that "sharing in the administration of justice is a phase of civic responsibility."

Examples of distinctive groups are: Black people (Peters v. Kiff, 407 U.S. 493 (1972)), women (Duren v. Missouri)/Taylor v. Louisiana), Mexican-Americans (Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U. S. 482 (1977)).

ISSUES IMPACTING JURY REPRESENTATIVENESS

Reasons vary as to why juries still lack the diversity of the communities from which they are drawn. Below are some examples of how certain processes may ultimately create less diverse jury pools.

COVID-19

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, court administrators have faced increasing challenges ensuring that juries are representative. The pandemic’s disproportionate impact on communities of color, elderly and lower-income individuals, and those with predisposed health conditions have exacerbated existing racial, socioeconomic, and gendered dynamics on juries. Given these trends, during the height of the pandemic, young white men became the most likely group of individuals to show up for jury duty. As vaccine rollout continues and the risk associated with participating in a jury trial decreases, these demographics are beginning to shift. Despite this, the systemic issue of unrepresentative jury populations remains – with COVID-19 merely bringing to light the existing inequities in an unjust system.

Learn more about how COVID-19 has impacted jury representation

Fundamental Issues with Jury Source Lists

Most jurisdictions draw their potential jurors from some combination of voter registration rolls and licensed drivers/state identification records. If voter registration rolls tend to be filled with older, white and more affluent individuals, one should expect the juries drawn from these rolls to be similarly older, white and more affluent. Similarly, every state has some version of a categorical exclusion from serving on juries for individuals who are incarcerated, or have a record of felony or misdemeanor crimes. These laws bar over 20 million people, reducing racial diversity by disproportionately Black and Latinx people (Prison Policy Initiative, 2021).

Jury Service is Cost-Prohibitive for Some

In other cases, jury service is difficult for those who don't have the means to take time off from work or transportation to the courts. If racial diversity tends to decrease as incomes increase, one should again expect juries to be less racially diverse. Some cities, like San Francisco, are attempting to address this problem with programs that increase pay to low-income jurors.

In Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986), the Supreme Court created a two-step inquiry in order to determine whether the use of peremptory strikes were racially biased. In what is now known as a Batson challenge, defendants may object to the use of peremptory strikes on the ground that they are being used to exclude a potential juror on the basis of race. In Georgia v. McCollum, 505 U.S. 42 (1992), the Supreme Court expanded that rule to bar criminal defendants from using peremptory strikes to exclude members of a jury on the basis of race. In J.E.B. v. Alabama, 511 U.S. 127 (1994), the Supreme Court banned strikes based on gender. Despite repeated admonishments from the Supreme Court regarding the systematic preclusion of certain groups from jury service, the practice continues across the country.

In 2010, the Equal Justice Initiative conducted a comprehensive study that showed that the racially biased use of peremptory strikes still persists. Indeed, in his prescient concurring opinion in Batson, Justice Thurgood Marshall cautioned that,

“any prosecutor can easily assert facially neutral reasons for striking a juror,”

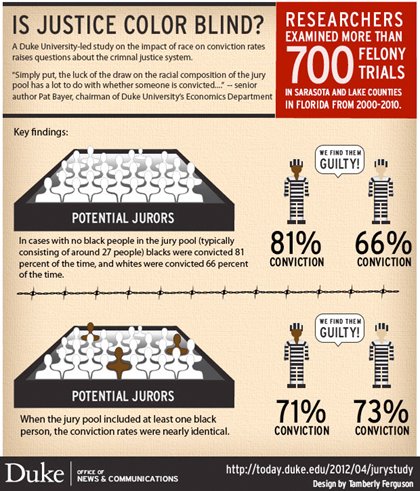

Study after study has shown that the discriminatory use of peremptory strikes has disproportionately eliminated black jurors. The detrimental impact of these practices cannot be overstated since black and other racial and ethnic minorities are over-represented as criminal defendants.

Importantly, research has shown that that diverse juries tend to deliberate longer, discuss more evidence and make fewer factual errors. One study in Florida indicated that all-white juries convicted black defendants 16 percent more often than white defendants.

Given what's at stake during the course of a criminal prosecution, it is immensely important that legal system stakeholders evaluate what challenges and barriers are impacting the representativeness of juries and work to effectuate change.